Why for-profit housing succeeds

when subsidized housing fails

By Thomas Irwin | March 15, 2024

In the first part of this series, I reviewed the one bright spot in Los Angeles’ efforts to increase housing supply and reduce housing costs – the success of for-profit developers in building homes under the city’s Executive Directive 1, which reduced barriers to building affording housing. In this piece, I’ll look at the specifics of how ED 1 succeeded.

Considering three categories (inadequate zoning, high costs and slow approvals), we can see how ED 1 has catalyzed a mini-building boom. What made the pathway so appealing was the ability to combine multiple reforms that addressed each of these specific barriers to homebuilding.

The first is obvious: ED 1 gives new housing a predictable timeline for approval, something unique and invaluable in Los Angeles. Developers have also expressed confidence that units offered below market rates will rent out very quickly once constructed given how much demand there is for lower-cost units.

But these projects have other advantages. Based on recent research, land-use expert Joseph Cohen May estimates that at least 85% of the proposed projects also benefit from one of two key zoning reforms: 1) the California state density bonus; or 2) LA City’s Transit-Oriented-Communities (TOC) program. While these programs are slightly different, they both share a common feature: they give developers a “density bonus” to construct more units on a lot than they usually would be able to under existing restrictive zoning codes.

California’s state density bonus is the more popular option for ED 1 projects due to AB 2345, a 2021 law that allowed 100% affordable projects to include unlimited density and three extra stories of height. These projects were feasible because the original version of ED 1 allowed flexibility in pairing ED 1 with these density bonus incentives. The added density and efficient use of land allow projects to spread out their fixed costs, even though units will rent below market rate. This allowance for more density is the most critical piece of making these new projects feasible for for-profit developers, according to several affordable-housing developers I interviewed.

Read Part 1 of Thomas Irwin’s

Free Cities Center series on LA’s housing reforms

Read the new Free Cities Center booklet,“Giving Housing

Supply a Boost.”

These laws have been on the books for several years, so why are projects suddenly coming online now?

Another layer to ED 1 has contributed to the building boom: relief from parking requirements that are often one of the most expensive line items in new housing. By some estimates, structured parking in Los Angeles can cost up to $55,000 per space. In 2022, California passed AB 2097, which allowed housing developments within a half-mile of a transit stop to have total flexibility in the number of parking spots provided. This opened up the potential for housing to be built at a much lower cost than before, and most ED 1 projects are opting for this flexibility. Many ED 1 projects are fully parking-free, significantly reducing the cost.

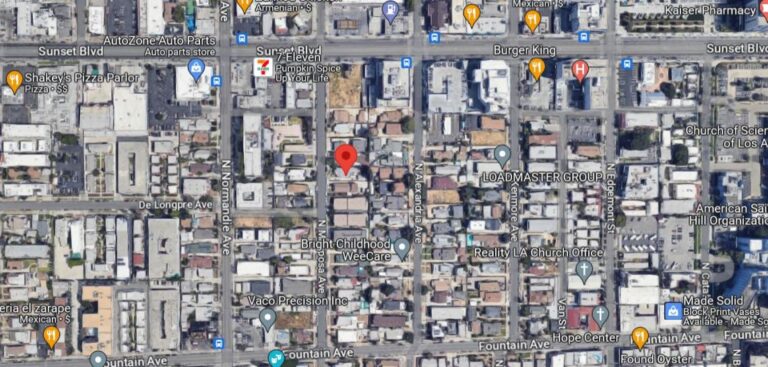

To illustrate this in a specific project, look at 1412 N Mariposa Ave., an ED1 project located in the city’s East Hollywood neighborhood. An Urbanize LA article describes the project as “a new six-story, approximately 20,000-square-foot building which would feature 73 studio apartments in a building without on-site parking.” Based on public information, the developer PAX Urban Partners has previously built market-rate and mixed-income housing.

So why, in this case, do they plan to offer 100% below market rate units? First, zoning reforms allow a taller, bigger and denser building than would typically be allowed. RD2-1XL zoning would limit development to two stories and three to four units. But by using the California’s density bonus law, the building grew to five stories and included 73 studio apartments.

Second, the building is taking advantage of parking reform to forgo the extra cost of building a parking garage, providing zero on-site parking spots. This arrangement may not work in all neighborhoods and for all potential residents, but in this context, it makes practical sense. The proposed building is in East Hollywood, one of LA’s densest neighborhoods. It is a 10-minute walk from a major metro stop on LA’s B line – putting most of downtown Los Angeles and central Hollywood a 25-minute or less train ride away.

Given the building’s studio units, it makes sense to bet that younger, economically-minded residents would be more than willing to live without a dedicated parking space in an area that’s close to jobs and entertainment. And, of course, with ED 1 streamlining, the builder is counting on a quick approval process, opening up a business model where revenue can be realized much sooner.

Many other projects follow this same playbook. 2528 E 1st Street in Boyle Heights will provide 51 apartments in a four-story building on a commercial lot without providing any on-site parking. Down the street, 2330 E 3rd Street, is a four-story, 53-unit project being built on a vacant low-density residential lot without any on-site parking. In Vermont Knolls in South LA, 7313 S. Figueroa Street has a seven-story, 145-unit project built on a commercial lot without providing any on-street parking. Reducing these parking requirement is resulting in a building boom.

In Part 3, I’ll describe the lessons that Los Angeles’ ED 1 success provides for other Western cities.

Thomas Irwin is a writer who works in the faith-based economic development field. He has worked with several housing and economic advocacy organizations in the region, and lives in East Los Angeles with his wife and two kids.