Much has been made of the decline of California over the last year, and not without reason—the Golden State lost 173,000 residents last year. Worse yet, that’s probably an improvement: by one estimate, 650,000 people left California in 2020. Indeed, as a result of population stagnation over the 2010s, we recently lost a Congressional representative for the first time in state history.

But not everywhere in California has accepted this fate. While cities like Los Angeles stagnate and regions like the Central Coast shrink, many cities and suburbs across the state continue to grow. In some cases, this is a matter of second-cities stepping up to the plate—in other cases, it’s a matter of far-flung suburbs absorbing families priced out of existing cities. Let’s take a look at what the numbers show.

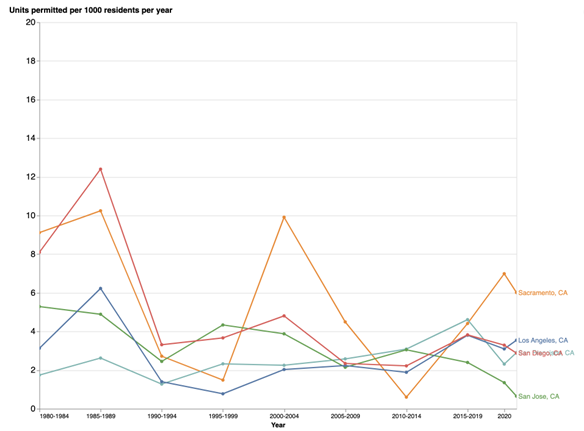

Sacramento. Of California’s five major cities, Sacramento is the fastest growing, and it isn’t even close. According to the 2020 census, Sacramento grew by 14.2 percent—fully 150 percent of the population growth rate of San Francisco, the next fastest growing major city. And it makes sense: with much of the Bay Area refusing to build housing, our relatively pro-growth capital remains a place where regular Californians can afford a home. Consider that Sacramento builds housing at 10 times the per capita rate of San Jose, and the shift becomes obvious.

The Booming Exurban Periphery. Nor was the past decade bad for California’s pro-growth suburbs. Over the past decade, the Orange County suburb of Irvine grew by roughly 100,000 residents, a nearly 50 percent increase in the overall population. In 2003, Irvine acquired the El Toro Marine Air Station and they’ve been busy developing it ever since. It isn’t all just cookie-cutter subdivisions, either—to a degree rarely seen today, Irvine builds a healthy mix of single-family homes, townhouses, and apartments.

Up in the Bay Area, Dublin filled a similar role. With most Bay Area suburbs simply refusing to build housing, suburbs on the inland side of the Diablo Range grew dramatically over the past decade. As with Irvine, this is largely a story of Californians reshuffling into places that are allowing housing to be built: over the past decade, Dublin built six to ten times as much housing on a per capita basis as inner suburbs like Palo Alto and Mountain View.

Exodus to the Interior. Of course, these booming coastal cities are largely the exception—much of California’s growth has been in the Central Valley, where cities like Bakersfield and Fresno have grown by 22 and 12 percent over the past decade, respectively. Indeed, by one measure, once-sleepy Fresno was home to the hottest housing market in the nation last year. Will they build enough housing to accommodate the booming demand, or will the housing crisis spread inland?

Back down the coast, sections of the Mojave Desert have similarly boomed, as families priced out of Los Angeles and the San Gabriel Valley have surged into suburbs like Palmdale, Lancaster, and Victorville. A similar boom is underway in the Coachella Valley, where suburbs like Desert Hot Springs and Indio continue to grow at a rapid rate. Imperial, once a sleepy farm town near the California-Mexico border in the state’s far southeast, sported some of the fastest population growth in the state.

~~~

What’s the common thread? Those places in California that still allow housing to be built are growing. Despite all of our problems and all the negative narratives about our state, many millions of people would like to move here, and many current residents would like to stay. California is still the Golden State—when we allow housing to be built, people can and do stay. Those cities and suburbs that continue to build and make the California Dream a possibility deserve high praise.

But that’s a rub: in so much of the state, cities and suburbs aren’t building, forcing many California families to move further and further out, enduring longer commutes and harsher climates. Many families might want that single-family home on the periphery, and that’s okay—small towns and deserts certainly have their charms. But many others might like to stay in cities like Los Angeles, or our state’s famous coastal climates. We should build enough housing to give every California family that choice.

Nolan Gray is a professional city planner, housing researcher at UCLA, and Pacific Research Institute fellow.