‘Urban growth boundaries’ make cities less affordable

by John Seiler

At a time when many Western officials are reducing housing restrictions to promote building and thereby ease the affordable-housing crisis, they also are embracing a policy that runs contrary to these goals. Most Western states continue to create Urban Growth Boundaries (UGBs), which limit growth and drive up the cost of housing.

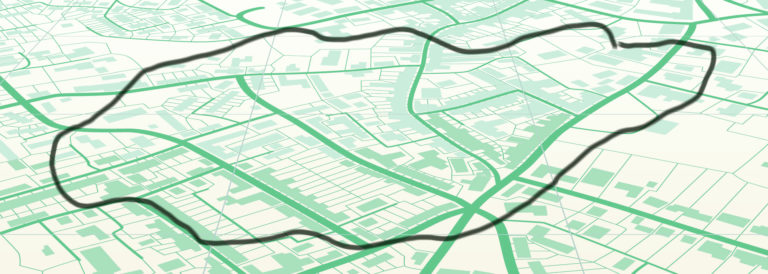

The Montana Department of Transportation defines UGBs as “geographic areas defined in plans or regulations as desirable and appropriate for growth during a defined period of time, usually 20 years. In order to encourage private investment, urban growth areas are considered a high priority for public infrastructure and services.” Generally, these boundaries limit growth on the outskirts of cities.

It’s ironic that even rural Montana has embraced the concept given the state’s abundance of open land, but UGBs have become something of a religion among government planning and transportation agencies throughout the West. Local or regional governments typically implement these plans – but state governments (especially in liberal states such as Oregon and California) sometimes mandate them.

The goal is to force growth into the existing urban footprint, as a way to promote urban living, save infrastructure costs and fight global warming (even though it’s debatable that density reduces climate change). In reality, UGBs promote the urban sprawl their supporters oppose. These boundaries inflate the value of existing properties. Homebuyers then leapfrog the boundaries to bedroom communities unaffected by the limits and commute back to the city.

We’ve seen that around Portland, Oregon, and the San Francisco Bay Area – two regions that have imposed some of the most-restrictive UGB regulations in the nation. In Montana, the city of Belgrade is something of a residential boomtown – as it is only 15 miles from the UGB-controlled college city of Bozeman. The problem is UGBs substitute government planning limits for market forces.

Just as you can’t fool Mother Nature, you can’t fool the market. Imposing artificial boundaries distorts the law of supply and demand, and benefits existing homeowners who already own homes inside the boundaries. Many of the West’s smaller cities have become enclaves for the very wealthy. With growth controls in place, service workers often must commute long distances because of the lack of affordable housing and these UGB-imposed limits on construction.

Smart Cities Dive described how Oregon enacted the first UGB law in 1973, with the passage of Senate Bill 100. Its goal was “protecting Oregon’s natural splendor from sprawl. Every community then had to develop its own long-range plan for managing growth, with Portland creating its urban growth boundary in 1979. Since then, the population of Portland has grown 60 percent, while the urban growth boundary has expanded just 14 percent.”

As a result, Portland quickly went from one of the nation’s most affordable major metropolitan areas to one of its least-affordable ones. “UGB locks in existing housing patterns,” said Michael Tanner, a senior fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute. To alleviate housing shortages, he added, “Essentially what you want to do is be able to build everywhere possible.” In California especially, “it already was hard to do infill housing in the core.”

“And if you’re also saying the outskirts can’t be used for housing, you’ve got a real problem,” Tanner continued. “In California, most of the growth is set by Local Area Formation Committees (LAFCOs). They are charged by law to have three considerations when they determine urban boundaries. One of those is the preservation of green space, second is to prevent urban sprawl and third is to preserve agricultural land. … (T)hey should be required to consider the provision of adequate housing on the same basis as those other priorities.”

Tanner commended the state for this year passing “very good legislation” advancing more housing. These included Assembly Bill 2097, which prohibits imposing minimum automobile parking requirements on specified on developments within one-half mile of public transit. Assembly Bill 2011 and Senate Bill 6 make it easier to convert commercial properties (such as vacant shopping malls) into housing developments.

But, Tanner said, incentivizing infill construction isn’t sufficient: “There’s a lot of resistance from the neighborhoods and the city governments. Even finding space in some of these urban areas is difficult to do because they’re already pretty well built out. So it makes sense to be able to expand on the outskirts of the city as well. But it’s deprioritized under the current arrangements.”

Despite these problems, various housing groups continue to push them. “Given the onslaught of climate change, urban growth boundaries may be one of the most equitable tools that municipalities have at their table,” wrote Isaac A. Gendler in a white paper for Abundant Housing LA.

Yet even Gendler is aware that UGBs could raise prices for the poor: “While urban growth boundaries certainly have their benefits, no public policy decision comes without drawbacks. Although these mandates might increase urban development within the city itself, it could lead to an overall decrease in available housing supply, shooting prices through the roof.” That’s a major drawback for a group committed to affordable housing and urban diversity.

His solution is partially right – cities should indeed “up-zone” urban areas to allow the market to provide more mid-rise and high-rise construction in the urban core. But Western states also need to allow the market to work throughout their metropolitan areas, including on the outskirts of cities. Few people might know much about this arcane term, but UGBs only exacerbate the housing crisis by limiting supply and driving up prices.

John Seiler is on the Editorial Board of the Southern California News Group.