Urban gentrification beats alternative of deterioration

John Seiler | March 23, 2023

Of all places, Houston – famous for its minimal zoning – now faces a “gentrification” crisis. Reported the Houston Chronicle, on February 22: “After years of concerns over gentrification in the Houston metropolitan area, the city’s Planning and Development Department introduced a proposed ordinance for creating conservation districts to the Houston City Council.”

The ordinance would be specifically designed to protect historic Black and Latino districts. “These communities are being gentrified; they are being wiped out,” Mayor Sylvester Turner warned. “Unless we take definitive steps to preserve these underrepresented disenfranchised communities, they will be no more.”

An impartial source, Merriam-Webster, defines “gentrification” as “a process in which a poor area (as of a city) experiences an influx of middle-class or wealthy people who renovate and rebuild homes and businesses and which often results in an increase in property values and the displacement of earlier, usually poorer residents.” “Anti-gentrification” means opposing this process.

Unfortunately, there seems to be no word for the opposite of gentrification – that is, when a neighborhood deteriorates. “Slumification” is too specific, and doesn’t include a general decline not necessarily into slums. But Rate.com notes, “There are actually a lot more neighborhoods where the opposite of gentrification is happening: middle- and upper-income residents moving out, lower-income residents moving in.”

I actually knew one such area well. It was the middle- and working-class neighborhood where my grandparents lived on the East Side of Detroit. Like them, many neighbors were immigrants who thrived with the burgeoning auto industry. Totally middle-class, the houses were bunched together, as is common in Midwestern big cities, with decent-sized back yards.

In the early 1960s, I remember my grandparents pointing out a nearby low-income housing complex of about 10 units. Those living there had to have intact families and “good character.” They stayed only until they “got back on their feet.” That was just before LBJ’s Great Society welfare programs, based only on income, broke up the families of the poor by cutting out fathers.

Grandma died in 1963. And when Grandpa died in 1974, his heirs – my father, uncle and aunt – sold the house for $6,000. That’s maybe $100,000 in 2023 money. I looked it up on Zillow. It was gone. Must have been burned down in one of the city’s infamous Devil’s Night arson plagues in the 1980s. In 1984, a record 810 fires consumed homes that once housed the middle-class workers of what once was called the Paris of the West. The houses still standing on my grandparents’ street list for an average of about $20,000. Vacant lots go for as low as $500.

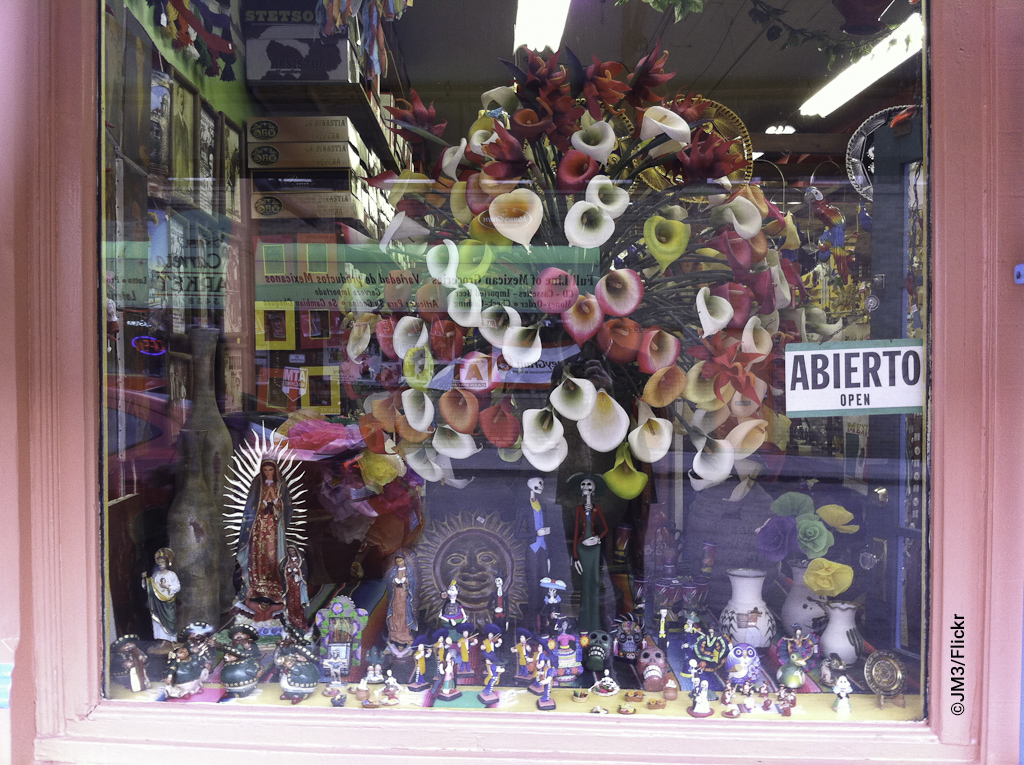

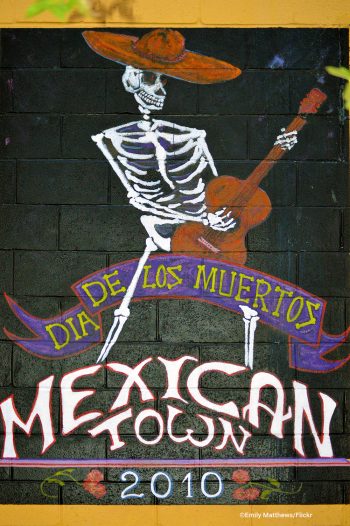

Wouldn’t the owners of those properties love to see “gentrification,” with their investments doubling or tripling in value? With the tax base rising to provide long-denied services, such as snow removal? With middle-class families moving back and driving out drug dens and gang headquarters? That’s actually happening in another part of the city, the Southwest, the mostly Latino area. When I took Spanish in seventh grade in 1967 at Franklin Jr. High School in Wayne, a suburb about 15 miles to the west, we actually took a field trip there to a Mexican restaurant. Now, that area is growing – gentrifying.

“Mexicantown thrives with bakeries, bars and restaurants,” reported Belt magazine. “However the small businesses extend outside of the commercialized Mexicantown area. The supermercados E&L and the Honey Bee La Colmena allow for the foods and traditions of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans to be easily accessible to the community. The Honey Bee La Colmena has significantly expanded since its founding in 1956, from four thousand square feet to fifteen thousand.”

In addition, “There are now sizeable Yemeni and Syrian populations in Southwest; people of different backgrounds are still looking to the area as a place of safety.”

I checked property values on Zillow, and in Mexicantown they’re still about the same as in my grandparents’ old neighborhood. That’s probably because there remains a lot of room for expansion to other neighborhoods in the area. Thus it always is: Decayed neighborhoods, if they’re lucky, become so cheap that newcomers arrive and fix them up – gentrification. So long as property rights are strong, that’s inevitable, and good.

There actually are some studies affirming gentrification. Basically, it’s part of the dynamism that makes Americans highly mobile. A 2019 Working Paper by Quentin Brummet and Davin Reed for the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia found, “Gentrification modestly increases out-migration, though movers are not made observably worse off and neighborhood change is driven primarily by changes to in-migration. At the same time, many original resident adults stay and benefit from declining poverty exposure and rising house values. Children benefit from increased exposure to higher-opportunity neighborhoods, and some are more likely to attend and complete college.”

For policy, it urged the following: “Our results suggest that accommodative policies, such as increasing the supply of housing in high-demand urban areas, could increase the opportunity benefits we find, reduce out-migration pressure, and promote long-term affordability.” That is – from my property-rights perspective, and specifically for California – enacting the reforms often talked about, beginning with the California Environmental Quality Act. Gov. Gavin Newsom just vowed to push CEQA reform after the First District Court of Appeals absurdly blocked the construction of housing in Berkeley for 1,100 students and 125 homeless.

In sum, the best way to ease the inevitable changes in neighborhoods is not to reduce property rights, but to increase them. Gentrification is a necessary and inevitable process of accommodating the ever-changing housing needs of a vast and diverse country. Even now, it reflects the spirit of Huck Finn, who urged us “to light out for the territory ahead of the rest.”

John Seiler is on the editorial board of the Southern California News Group.