Although I usually drive, sometimes I take the bus in Orange County, the last time a year ago. As you might expect in car-centric Southern California, almost all the other riders were poor people, some no doubt recent immigrants of unknown official status. I know many recent immigrants, and the first thing they work to get is a vehicle, usually a pickup truck.

On my rides last year I was vigilant due to reports of increased violence on mass transit. The Orange County Transportation Authority still required masks. Every passenger except me was hunched over entranced in an iPhone or listening to something through earbuds. Although the pandemic measures made me cautious, I didn’t feel unsafe. I never have seen a sheriff on a bus; the system is patrolled by the Transit Police Services of the Orange County Sheriff’s Department.

A different policing system is being advanced in the neighboring, gigantic Los Angeles County Metropolitan Authority, which serves 10 million people, and has suffered serious problems from crime and homelessness. The board of directors in March first announced hiring 300 unarmed Metro Ambassadors, then approved hiring 48 new Transit Security Officers.

It also said it would “re-negotiate and potentially extend for up to three years its contracts with its law enforcement partners to ensure more visual presence on the system, while it evaluates the feasibility of creating its own in-house public safety department.”

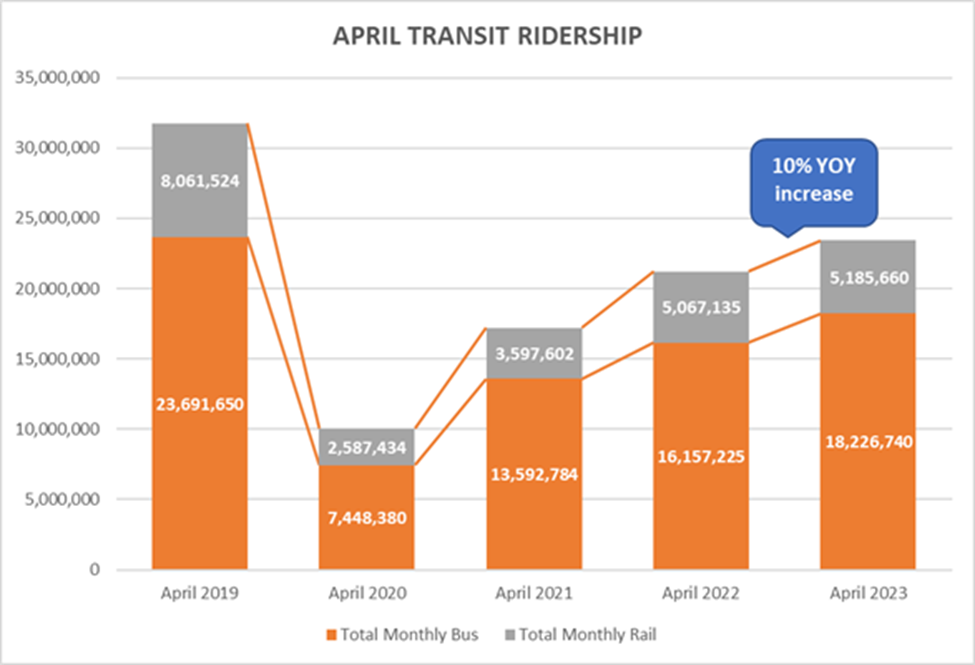

On June 20, reported the Los Angeles Times, “the board unanimously voted to develop a blueprint for the new police agency, a move that could end the longtime contracts with local law enforcement.” Although ridership has recovered somewhat from the COVID crash, it still is down about 26% overall for buses and trains combined, especially on weekday ridership. Here’s Metro’s graph for April:

And despite the lower ridership, a May 30 analysis by ABC 7 News found, “Over the last 12 months, violent crime reported by LAPD on Metro properties increased 14% to 16% higher than pre-pandemic levels.”

A big problem stems from Metro making ridership free during Covid, a mistake also made by Bay Area Rapid Transit. “Transit systems that switched to zero fares during the pandemic found that homeless people and criminals flocked to their rail transit systems as rolling flophouses, which deterred many others from riding them,” Bob Poole told me; he’s the director of transportation policy at the Los Angeles-based Reason Foundation.

Will the shift to a separate Metro police agency reduce crime and bring back riders?

“Bringing additional layers of public safety in-house will give Metro a greater ability to reliably deploy personnel with the training and capabilities to respond to the variety of incidents that occur on our transit system,” said Hilda L. Solis, a Los Angeles County supervisor and Metro board member. She also served as labor secretary under President Barack Obama and was a member of the House of Representatives. I met her in the 1990s when she was in the state Senate and our Orange County Register editorial board interviewed her. She seemed a reasonable politician looking for solutions.

She was seconded by Baruch Feigenbaum, the senior managing director of transportation policy at the libertarian Reason Foundation. “Creating a dedicated police force could be a good solution,” he told me. “Most large transit agencies have a dedicated police force. And it is easier from an administrative perspective.”

In moving to the new model, Metro also has to deal with the national concern over police abuses following the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020, and the subsequent unrest in many cities. At its March meeting, the Metro board also approved what it called Bias-Free Policing and Public Safety Analytics policies. It said, “These policies are meant to set clear expectations and standards to help Metro eliminate potential bias in the way the transit system is patrolled. Previously, Metro found evidence that suggested racial bias might have been a factor in citations given to riders. Metro’s goal is to eliminate any form of bias against its riders.”

Feigenbaum said, “Transit police are more subject to complaints of excessive force or failing to do their jobs. There might be more accountability with an outside agency,” because the board more directly could hold it accountable for bad performance.

He said good policies for such a police agency include:

- Put officers at random stations and on random buses and trains. “If officers are at the same place every day, perpetrators are going to figure out quickly where they can and cannot commit crimes. Ultimately, police cannot be everywhere.”

- Video surveillance is an effective deterrent, “but raises privacy questions.”

- Punish crime. “The highest rates of transit crime are generally in the cities with the highest rate of crime overall.”

- Model European and Asian cities, which generally have more surveillance, more officers per rider and more crowded systems. With more people on a bus or rail, perpetrators stay away. Because if anything they’re more likely to be caught and detained

Reducing crime definitely would increase ridership. “The rough rate I have seen is a pattern of violent crimes (rape, assault, murder) decreased ridership by 5%-10%,” Feigenbaum said. “But it depends on the location, ridership, etc. Crime is definitely a much bigger problem post-COVID, but that mirrors society. Many disturbances cause people to quit or stay away from transit.”

Given the commitment of California officials to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by getting people out of their cars, one would think solving the Metro crime problem would be near the top of priorities. At least they are starting to address it.

The policing situation also is part of the overall crisis of homelessness and high housing prices. Which brings up another irony. Although mental health is a major part of the homelessness problem, housing prices are too. Mitigating that problem, such as through the perennial need to reform the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), would reduce overall crime, including on mass transit. But little is happening on that front, either.

Finally, this approach to reducing transit crime is part of the overall inability of many levels of government to advance coordinated solutions to problems. Everything is piecemeal. Bonds to build housing for the homeless at expensive Project Labor Agreement rates, cutting greenhouse gases, reducing crime, police reform, dealing with mental illness and drug abuse – all are thrown into the air like confetti. Until there’s a comprehensive vision and coordination, there will be little progress at any level.

John Seiler is on the Editorial Board of the Southern California News Group. Write to him at [email protected]