In 2019, the San Francisco Chronicle published an in depth look at juvenile justice in California. So struck was the paper by the decline in juvenile crime, the article was titled, “Vanishing Violence.”

The numbers were indeed striking.

In 1995, juvenile homicides stood at 382. By 2017, the latest year of statistics for their report, the number had dropped to 63. Similarly, reported felony arrests declined from 22,601 to 7,291 during the same timeframe. The article declared California’s apparently overbuilt juvenile halls were “near-empty monuments to a costly miscalculation.”

The State of California followed suit and ultimately closed the Division of Juvenile Justice along with its network of juvenile facilities once known as the California Youth Authority (CYA). All of its wards were paroled out or transferred back to the counties from which they had been sentenced.

From the Chronicle story:

In human terms, a Chronicle analysis shows, the downward trend in violent crime has resulted in 4,700 fewer juveniles slain in California during the past 2½ decades; 150,000 fewer arrests for rapes, assaults and other violent crimes that didn’t happen; and hundreds of thousands of youths not booked into juvenile hall.

What the Chronicle and the reformers fail to understand is that the decline had been set in motion years earlier when prosecutors were allowed to assess the seriousness of juvenile cases and appropriately charge violent youthful offenders as adults.

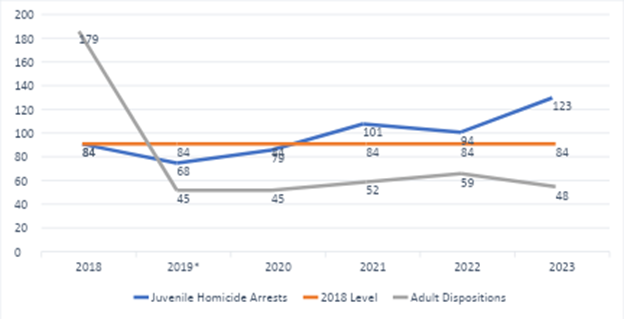

Contrary to the Dickensian predictions of the opponents of so-called “mass incarceration,” in 2018, the last year under the previous system of prosecutorial discretion, just 179 juveniles were charged as adults – the vast majority of whom were 16 and 17 years old. Of those, 137 were convicted and only 95 were sentenced to DJJ (CYA) or state prison.

In 2018, the decline ended as the last political nails were driven into the juvenile justice system coffin with the enactment of SB 1391 and voter-approved Prop. 57.

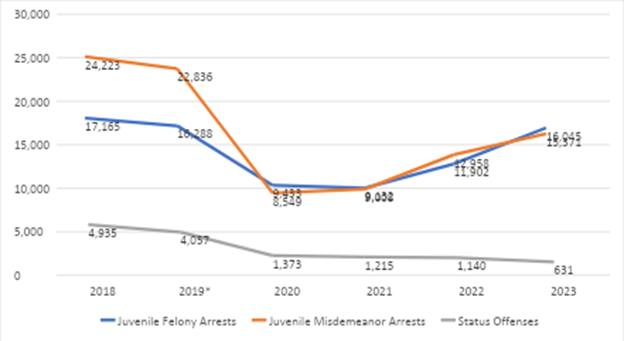

Juvenile Arrests

Passed in 2016, Prop. 57 was designed to allow for the release of rehabilitated non-violent adult offenders. The authors of the measure, fearing that including the prohibition of prosecutions of juveniles under the age of 16 would scuttle the proposition, specifically leaving that issue out of the measure. SB 1391, passed by the state legislature and signed by Gov. Brown changed that and prohibited the charging of individuals under age 16 as adults and further, shifted the decision to charge 16 and 17-year-old offenders as adults to judges, most of whom have been appointed by former Gov. Brown and Gov. Newsom.

The results were predictable, since 2018 the number of juvenile homicide victims has increased every year except one, peaking in 2022 at 174 and then dropping to 147 in 2023.

The number of murders committed by juveniles has also increased, growing from a historic low of 68 in 2019 to nearly doubling to 123 in 2023. During this two-fold increase in murder arrests, the number of juveniles referred to adult court has dropped from 179 in 2018 to just 48 in 2023.

Juvenile Homicide Arrests and Adult Prosecutions

Source: California Attorney General’s Office

In 2019, there were 22,836 felony arrests and just a year later in 2020 those numbers dropped to 9,433, for a decrease of over 59 percent. But by 2023, felony arrests had climbed back to 16,045. Only status offenses (crimes that are only crimes because of the age of the offender) have maintained their steady decline. This is because it’s unlikely police departments are arresting juveniles for curfew violations or shoulder tapping anymore.

While the increase in juvenile murders has been dismissed as anomalies by advocates of decriminalization and decarceration, the consequences have been far from anomalous.

Two recent cases in Los Angeles County provide examples. In 2019, 17-year-old Shanice Amanda Dyer, a member of the notorious Crips criminal street gang, allegedly murdered Alfredo Carrera and Jose Vasquez as well as injuring a third victim. Carrera was an expectant father and Vasquez was an aspiring UC Irvine astrophysicist.

But Dyer caught a break with the election of George Gascón as District Attorney of Los Angeles. Gascón issued a policy memo prohibiting the prosecution of any juvenile as adults, as well as the use of gang or firearms enhancements.

Tried as a juvenile, she was released by her 25th birthday and returned to Los Angeles County to murder again. This time the alleged murder occurred in Pomona, where she reportedly lured 21-year-old Joshua Streeter to a strip mall where he was murdered. Had she been tried as an adult for a double murder, she would have been eligible for a life sentence and Streeter may still be alive.

Then there’s the 2018 case of 16-year-old Denmonne Lee, who allegedly shot and killed Marine Corps veteran John Rug during the robbery of a gas station in Antelope Valley. As his case wound through the justice system, Lee also benefited from Gascón’s prohibitions and was sentenced as a juvenile Lee allegedly responded well to rehabilitation programs and was released by his 25th birthday – soon after he was arrested for allegedly killing Eric Ruffins last April.

As arrests and murders increase and prosecutions stall, it’s a legitimate question to ask policymakers how long this policy will continue.

Steve Smith is a senior fellow in urban studies at the Pacific Research Institute.