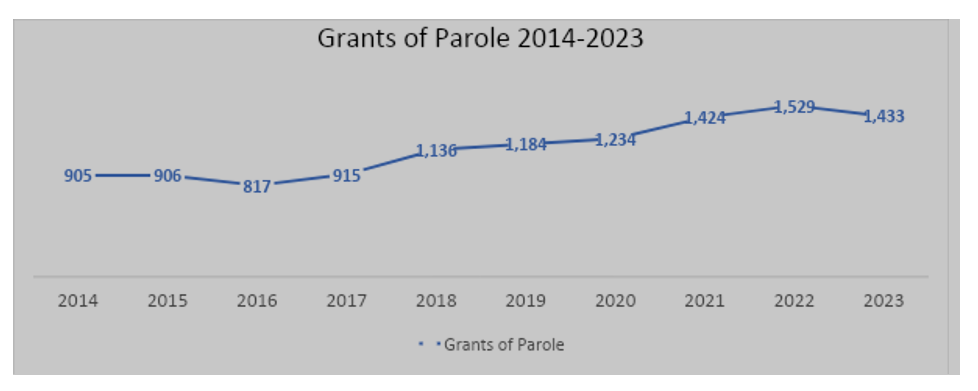

Yet today, the overwhelming majority of California’s violent inmates are already or will be eligible for a parole hearing and potential release. And they are being released in record numbers.

It is a common misconception that California’s prisons are full of non-violent offenders. That ended with the passage of AB 109 in 2011 and a result of which the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) has released or transferred to county jails thousands of so-called “triple-nons”: non-violent, non-serious, and non-sexual offenders. From 2011 to 2024, the state prison population declined by 47 percent.

AB 109 releases were multiplied when Prop 57 further accelerated the release of violent offenders through the use of early release credits, many of them bogus.

Of the 92,251 prisoners currently serving time, over 75,000 are violent offenders and only 5,725 are not eligible to be paroled.

Breaking this down, 625 are still in custody under sentence of death and 5,100 are serving life without parole sentences, more commonly known as LWOPS. The LWOP inmates qualified for that sentence because their crimes involved a “special circumstance” sentencing enhancement.

“Special circumstance” murders can include killing to avoid capture; the murder of a witness to prevent their testimony; the infliction of torture; the murder of a public safety officer, judge or political official; murder based on a victim’s protected status under the hate crime laws; murder during a kidnapping, robbery rape, or arson; drive by killings, those committed as a member of a criminal gang, and the use of bombs or explosives.

Thirty years-ago, many prosecutors might have sought the death penalty in special circumstances cases but today the death penalty, while still a potential sentence, is rarely sought by prosecutors. In 2023, just 3 inmates entered CDCR custody under sentence of death.

The alternative sentence to death, and what many death penalty opponents suggest is a compassionate alternative that protects public safety, is LWOP.

49 states, the federal government, and the US Military have all adopted the LWOP sentence including 27 that still allow death sentences.

The inevitable conclusion of a life sentence is death. Despite the protestations of prisoner rights advocates, health care in prison has reduced prisoner mortality to half what it is for the rest of the population. This means they are growing old – but not less dangerous.

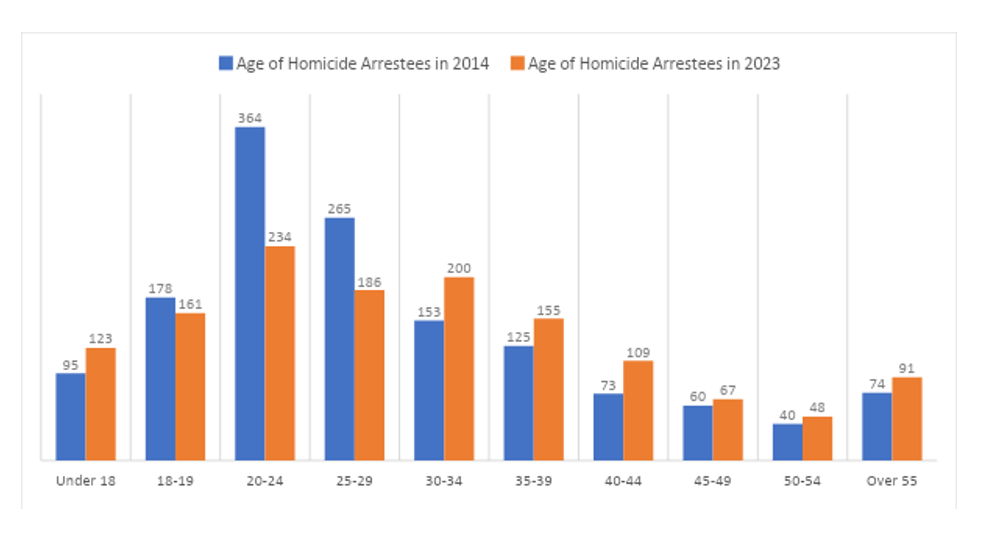

Sen. Cortese would have you believe that “elderly” inmates cease to become a criminal threat and that’s probably true when they cease to be ambulatory. The problem is that Cortese considers someone over 40 as elderly. His website states, “research overwhelmingly shows that people age out of violent crime.”

His research is ten years out of date.

Cortese states, “a person’s propensity toward violence peaks in their twenties (before the full development of the prefrontal cortex) then rapidly declines by age 40, and continues to fall with age.” That might be true of shoplifters and car thieves. In the case of murder, he couldn’t be more wrong. Older offenders beginning at age 30 commit a higher percentage of murders and that number is increasing.

In 2014, the number of suspects arrested for murder under the age of 40 was 1,180 while the number arrested over the age of 40 and over was 247. In 2023, the numbers changed. 40 and overs now account for 315 murder arrests, an increase of 27.5 percent. This includes inmates over 55.

The biggest decline is actually in the 18-29 age demographic, who Cortese considers the most dangerous due to their “underdeveloped prefrontal cortex.” Their arrests actually dropped from 807 in 2014 to 581 in 2023, a decline of 28 percent.

Upon taking office, Los Angeles District Attorney George Gascón prohibited filing special circumstances murder and the word got out. As reported in the Los Angeles Times, during a recorded jail phone call, convicted murderer Aariel Maynor bragged, “I’m going get out of jail. I’ll probably do like 20 … 25 years, get out, you feel me (sic)?”

When faced with the public backlash, Gascón ignored his own policy not to charge special circumstances and Maynor was convicted and sentenced to 150 years in prison.

Under Cortese’s bill, the 30 year-old Maynor would be eligible for release by his 55th birthday to join the increasing ranks of California’s aging killers.

The State Legislature should consider this when debate on SB 94 resumes.

Steve Smith is a senior fellow in urban studies at the Pacific Research Institute, focusing on California’s growing crime problem.