Not one of the ten bills pending in the state legislature even mentions dangerous drugs.

The CDAA ballot initiative addresses the complexities of prosecuting serial and repeat thieves and refocuses on the root cause – increasing dangerous drug addiction and the systemic, pharmacological, and economically compulsive violence that contribute to those deaths and economic losses.

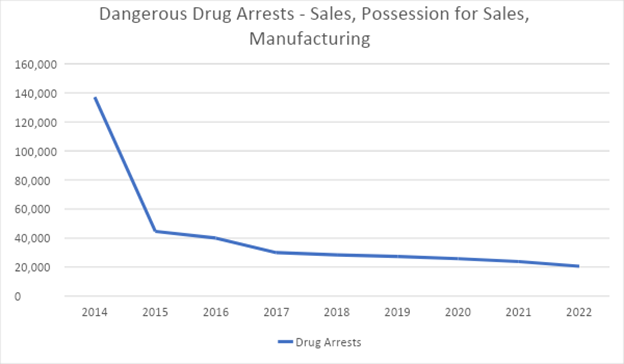

Declining drug arrests are due in part to Prop 47’s reclassification of dangerous drug possession as misdemeanors. Even when arrests are made, charges are usually dismissed through plea agreements requiring offenders to participate in treatment programs – programs that often do not hold them accountable if they don’t participate.

Proponents consider declining arrests as a measure of success and from a purely de-carceration stand point it is. But following that line of logic, a state could decriminalize most anything and experience a decline in arrests, prosecutions, and incarceration and claim success. However, the consequences in other areas would be dire indeed.

In addition, Prop 47 proponents’ use of national incarceration statistics for so-called “non-violent drug offenders” that were incorrectly attributed to California led to the oft heard refrain that our prisons were full of non-violent drug offenders. In 2014, a scant 7 percent of CDCR prison inmates were incarcerated for dangerous drug offenses. Today, they represent 2 percent of incarcerated individuals.

Going all the way back to 2000 with the passage of Prop 36, through to the passage of Prop 47 in 2014 and continuing to today, public sentiment runs strongly in favor of rehabilitation vs incarceration. Yet, data may now show that addicts are enabled by a system that offers few incentives for treatment, almost no deterrence, and may actually encourage drug use through harm reduction and normalization/de-stigmatization strategies that in some cases portray dangerous drug use as fun.

In 2021, Oregon attempted a similar experiment to Prop 47 when it implemented Measure 110, which decriminalized drug possession for personal use. Individuals found in possession of dangerous drugs faced fines of $100 or voluntary participation in a health assessment in person or over the phone. That year, Oregon experienced 1,171 fatal drug overdoses. In 2022, overdoses increased to 1,363 and by the end of 2023, CDC estimates put the number of dead at 1,809. This is a three-year increase of 54 percent. Like in California, arrests in Oregon plummeted and over the course of the first year decreased by 60 percent.

Does de-criminalization and poorly designed harm reduction programs cause increasing overdose deaths? University of Toronto researcher Noah Spencer took a look at overdose deaths in Oregon for the first year after Measure 110’s passage and concluded that yes it does.

In that study, Spencer writes:

I find that when Oregon decriminalized small amounts of drugs in February 2021, it caused 181 additional drug overdose deaths during the remainder of 2021. This represents a 23% increase over the number of drug overdose deaths predicted if Oregon had not decriminalized drugs.

Spencer goes on to report that, similar to the nine-year decline in arrests in California, Oregon has experienced an arrest decline of 60 percent from 2021 and 2022, while the US decline comparatively was 30 percent.

Writing in the Journal of Public Economics, Analisa Packham concluded that needle exchange programs, despite reducing the spread of communicable disease, actually increased the number of fatal overdoses.

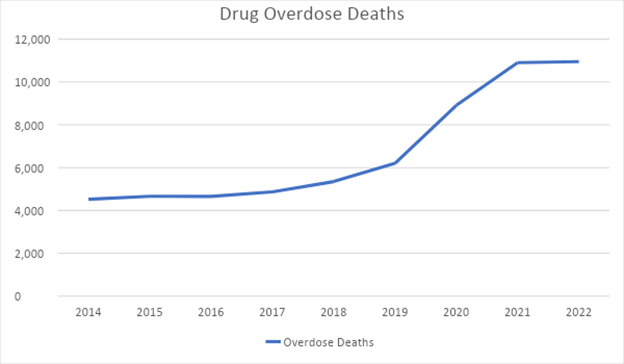

Though Prop 47 promised outpatient or “street treatment” and “safer use”, without incarceration as a deterrent strategy, Centers for Disease Control data finds that drug overdose deaths in California are increasing and are predicted to hit 12,710 when all of the 2023 data is in. This builds on an upward trend in overdose deaths that have already increased 142 percent since 2014.

Conversely declining arrests and incarceration rates are exactly as intended by Prop 47’s proponents.

Put another way, the number of people killed by drugs in the nine years from 2014-2022 is over 60,000. Yet if the number of overdoses had remained at their 2017 levels, the total number of deaths would have been 24,340 over the same six years.

After experiencing just three years of increasing dangerous drug use, fatal overdoses, and the increase in thefts that almost always accompany a spike in drug use, Oregon said enough. Measure 110 was overturned this year.

The question that Californians should be asking themselves today is what the acceptable level of death is, and how many will be allowed to die under our failed 10-year Prop 47 experiment.

Steve Smith is a senior fellow in urban studies at the Pacific Research Institute, focusing on California’s growing crime problem.