Private cities bypass ossified governments.

Will California follow?

By Thibault Serlet

California’s public discourse about urbanism has become extremely pessimistic. A glimpse into some of the large-scale private cities – generally known as Special Economic Zones, or SEZs – popping up in developing countries might offer us some well-needed hope.

Californians now face increasing government corruption, rising crime rates, lack of housing, hostile environments for business, and long term poverty. The current state of urban decay is giving Americans their first taste of the challenges billions of people in emerging markets face on a daily basis.

Paradoxically, as the severity of these issues is increasing in America, they are slowly being solved on the other side of the world. United Nations and World Bank statistics reveal that global poverty has declined by 20 percent over the last decade, almost entirely in emerging markets. There are many causes for this such as improvements in technology, liberalization of many emerging-market economies, and demographic shifts.

One under-appreciated cause is the emergence of private cities.

The concept of a private city is self-explanatory: It is a city that is built, operated and funded by entrepreneurs rather than the government. Instead of mayors, they have CEOs. Instead of city councils, they have shareholders. Instead of taxpayers, they have tenants and investors.

The Charter Cities Institute, a think tank that studies alternative types of urbanism such as private cities, recently published a map documenting dozens of these cities around the world. The United States even tried a similar approach in Sandy Springs, Georgia.

Private cities are important because they can show Californians a different and better way forward.

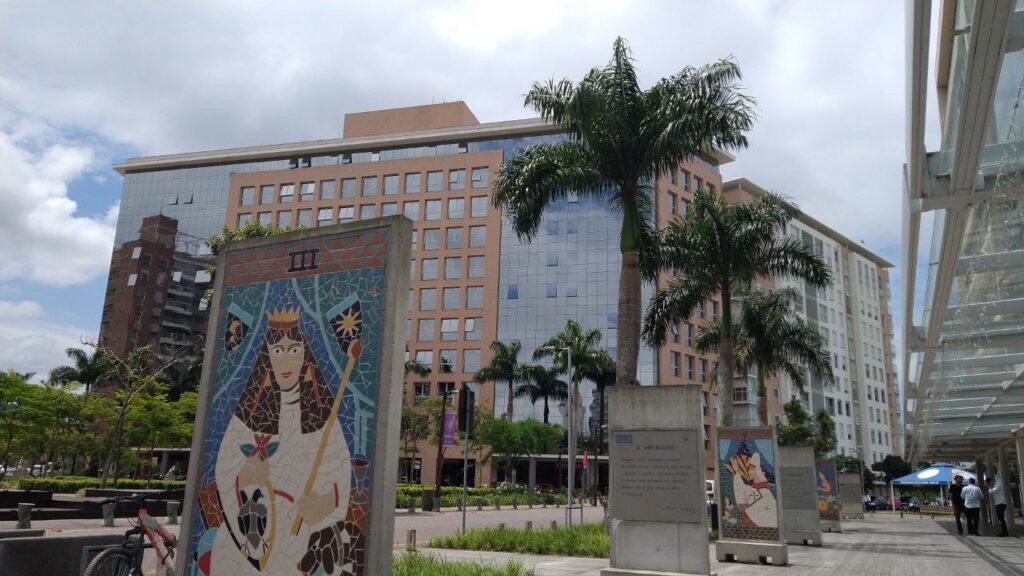

Pedra Branca, Brazil

One example of a thriving privately built city is the Pedra Branca Creative City.

Pedra Branca (literally “white rock”) is located in the state of Santa Catarina, in the south of Brazil. Initially, the city started off as a small farm owned by the Gomes family. The Gomes family realized that the area had a lot of potential, because it was in the safest region of Brazil, and close to the major city of Florianopolis.

In 1999, the Gomes family parceled out their farm into 2,000 plots to create “small urban villages.” From Day One, the Gomes family knew that they didn’t just want to have an ordinary real estate development – but wanted to attract more innovative industries. They lobbied for universities to open a campus, and finally got one of the largest local private universities, Unisul, to agree to open a campus on their land. After the university announced the creation of a campus, Pedra Branca grew rapidly. From 1999 to 2005, they sold 200 to 300 plots per year.

In 2005, the Gomes family realized that they wanted to take their development to the next level. They raised capital from American real estate investors, and began focusing on attracting industry to a newly opened tech park. Because Pedra Branca offered high quality infrastructure, scenic vistas and security, it immediately succeeded in filling up nearly all available lots in its tech park.

Ten years later, in 2015, the Gomes family sought to further expand their land, and began buying up adjacent lots. They realized that there were many local airports that struggled due to a lack of aircraft storage space, so started to build and rent aircraft hangers. This, in turn, began to attract airplane manufacturers. Now, the Aeropark has 331 commercial lots and 44 hangar lots.

One of the biggest infrastructure problems in the region is water management. As of 2020, only 47.7 percent of households in Brazil have access to sewage; whereas 100 percent of homes in Pedro Branca have sewage. Sewage and water is entirely managed by the Pedra Branca Water and Sewage System.

Waste Management is also a problem. Pedra Branca has a fully private waste system, and sends less than 10 percent of its trash to landfills. By comparison, San Francisco sends 27 percent of its trash to landfills, and London sends 50 percent to landfills. Most of the trash in Pedra Branca is sorted and burnt to generate electricity.

The growth of industry created a demand for high-quality housing. The Gomes family invited real estate developers to build a range of options, ranging from high-end luxury condominiums to affordable housing for workers.

Pedra Branca has been a huge commercial success. All lots have been sold. It is now home to roughly 40,000 residents, with many more commuters working there during the day. It has 700 apartments and 400 offices. In 2004, one square meter of real estate sold for $500. The price has tripled to $1,780.

Pedra Branca has many important lessons for California.

Because all infrastructure, security and development is private, the owners have an incentive to maintain and upkeep it. More importantly, this infrastructure doesn’t cost anything for the taxpayers. The owners of the project want to attract as many businesses as possible. To do this, they need to make sure that the infrastructure works.

Californian zoning and land-use laws would have made Pedra Branca impossible. Pedra Branca was built on a farm. The only reason why the city could emerge was because its founders were allowed to develop farmland. If Pedra Branca’s land had been designated under California’s A-1 Light Agriculture zoning rules, such a project would not have gotten off the ground.

In California, even if a project like Pedra Branca succeeded, it is likely that it would attract the ire of local officials and activists. As reported by the Pacific Research Institute, the Californian NIMBY attitude pushes governments to oppose all large real estate projects ranging from university campuses to Disneyland.

Luckily for Pedra Branca, the Brazilian government did not react the same way. The government instead decided to encourage the project, granting tax breaks for tech companies that chose to relocate there.

Songdo International Business District, Korea

The Songdo International Business District is a new city project built outside of Incheon, in South Korea.

In 2003, the South Korean government decided that they wanted to promote measures to increase economic freedom. The government created several “Free Zones” to increase the ease of doing business for foreign investors.

First, the Korean government concluded that taxes were especially burdensome for new businesses, which still lacked the ability to pay for expensive legal services. Companies inside of Korean Free Zones are exempted from most taxes for their first five years of operation, with some exemptions (such as property taxes) lasting up to 15 years.

Then, the South Korean government realized that whenever businesses needed to import or export goods, they needed to interact with a large number of government agencies. Each government agency had its own separate mandate, resulting in a confusing web of overlapping and competing responsibilities.

The government created a “Single Window.” Instead of interacting with multiple government agencies, businesses only need to go through one place. The Single Window also has an online user interface, so many government functions no longer require dealing with human officials.

Companies in South Korea Free Zone are also exempted from many of Korea’s labor laws. Korean labor laws can be burdensome. One requirement is for companies of a certain size to employ disabled or elderly workers. Unpaid leave is also illegal.

Finally, Free Zones offer a very wide range of other free-market-oriented reforms. Notable ones include exceptions from capital controls, special visa waivers and exemption from local zoning laws.

Immediately, investors from the New York real estate development firm Gale International saw potential in the South Korean Free Zones. They came up with the idea of creating a private city that would offer ultra-efficient private services that would normally be offered by municipal governments.

Finding a good location for the private city was difficult. South Korean Free Zones were created in areas that were already built up. Finally, investors came up with an idea: they would build on the sea. Incheon is a coastal city and had a lot of sandy semi-submerged areas. Gale International began reclaiming the land, building an artificial platform on the coastline.

The city covers an area of 2.5 square miles. It is home to 185,000 permanent residents. Thousands of businesses relocated to Songdo. Most notably, Songdo is home to a significant pharmaceutical industry – Celltrion, Samsung Biologics and Binex all have facilities there. Four universities have opened campuses in Songdo, including two American universities (George Mason University and University of Utah).

The project was extremely expensive – ultimately costing 40 billion U.S. dollars. Gale International partnered with the Korean steel manufacturer POSCO and American investment bank Morgan Stanley.

The city has a wide variety of unusual and technologically advanced municipal infrastructure pieces. This is possible because the SEZ fully privatized municipal services. It features a pneumatic waste management system, which sucks trash through underground tubes. Waste trucks are only used for particularly large or unusual trash. The city’s water system collects and harvests rainwater from all available surfaces. To attract more residents, the city’s developers also built half a dozen high-quality private schools, which the children of residents can attend for free.

All of the city’s systems are fully computerized. A central computer systems controls everything from parking spaces to the movement of fluids under the concrete. Additionally, residents can access all municipal services through a smartphone app.

Ironically, few of the technologies used by Songdo were developed in South Korea. Instead, most came from the Silicon Valley. Such a city would never be possible in California. The United States – and California in particular – would never offer the market-oriented regulatory concessions that made Songdo attractive for investors.

Would Private Cities be Viable in California?

Not for now, but maybe in the future.

Creating a true private city would be impossible in California. First, Californian cultural attitudes are generally hostile towards free markets. Instead of prioritizing growth and efficiency, Californians prioritize equality and fairness. Second, California has many entrenched special interests that would stand to lose from private cities. PG&E likely would oppose private power grids; the California Teachers Association likely would oppose Songdo-style private schools; the California Water Service likely would oppose private water grids, etc. Finally, there would be too many concerns about protecting California’s natural environment.

Interestingly enough, there are some California precedents for private cities.

During the 1950s and 1960s, California was home to many private cities. Irvine, in Orange County, was initially built by a private real estate development company in 1953. The town’s growth exploded after the University of California built a campus there. For a long time, its roads, electrical grid and water system were fully privately funded and managed. In many ways, its early growth story is similar to that of Pedra Branca. The town is still partially privately managed by the Irvine Company, although in 1971 it voted to become an ordinary city.

Many large universities in California already have private roads, their own police and fire departments, and are exempted from many municipal and county-level laws.

Stanford is home to 17,000 students, and 2,300 members of faculty, many of whom live on campus. Anyone who has ridden a bicycle from Palo Alto to Stanford’s campus can attest that when one crosses into the campus, the roads go from rough and bumpy to smooth and well maintained. Although Stanford University’s police force is a public agency, much of their funding comes from the university. In 2020, the school paid $33.5 million to build a new police building on campus.

We can view master-planned communities as an intermediate step in between ordinary cities and full-fledged master-planned cities.

There also are many master-planned communities. Around 40 perecent of new homes built in California are in master-planned communities. Some can be quite large. The Preserve, in San Bernardino County, has 8,100 homes. Shady Trails, also in San Bernardino County, has 1,100 homes.

Private cities are the market’s response to inept and incompetent government. When the police fail to protect citizens, they turn to private security. When fire departments don’t stop homes from burning down, fire suppression becomes the job of insurance companies. When the electrical grid fails, private power companies step in. Orange County built privately funded toll roads when the state wouldn’t expand freeway capacity.

As California’s cities become increasingly unlivable, the demand for private cities grows.

California’s largest planned community – Ontario Ranch, in San Bernardino County – is expected to have 47,000 homes and 162,000 residents when it is complete in 2037. It is being built by Brookfield Asset Management, one of the largest real estate developers in California. It remains to be seen whether the project ever materializes.

Despite increasing demand for affordable housing, the city of San Diego did not approve any new master-planned communities from 2006 until 2021. Then, in 2021, the city approved nine new master-planned communities.

Private cities becoming more relevant in California

Private cities are not yet relevant in California. California does not yet have the type of extreme poverty that makes these developments viable.

Current trends may change that. Private cities appear when emerging markets start developing rapidly, but are rare in developed countries. They either need to be built on a greenfield site, or in a highly decayed urban landscape, such as a slum.

Tech companies are leaving for other states, crime is increasing and the economy is stagnating. This will result in significant urban decay. Assuming that these trends continue for another 20 or 30 years, then the stage will be set for large-scale urban redevelopments – and for private cities.

When California becomes an emerging market, then private cities will emerge.

Thibault Serlet is the Director of Research at the Adrianople Group, a business intelligence firm that helps investors finance the creation of new Special Economic Zones. He is the architect of Open Zone Map, the world’s largest map of free zones, as well as the Charter Cities Institute’s New Cities Map. Previously, he advised for Pronomos, a venture capital fund that invests in new cities. He also founded the Startup Societies Network. His research is used by groups such as the World Bank, the Kiel Institute, the London School of Economics, Beijing University and US Air Force Intelligence. His writing has appeared in Reuters, FDI Intelligence (Financial Times), the Diplomat, Geopolitics Magazine, and elsewhere. He also writes a weekly blog, where he reviews books about economic history.