California has been a huge recipient of one-time federal COVID-19 dollars for education, with $23 billion pouring into the state’s coffers from Washington.

On top of this federal funding, California public schools have received $18 billion in one-time state funding to address pandemic-related issues.

Unfortunately, while some California public schools have spent these funds to address student-learning needs, many have not spent their tax dollars well.

An investigation last year by CalMatters found that California public schools “had wildly different approaches to stimulus spending—from laptops to shade structures to an ice cream truck,” with no central database “to show the public exactly where the money went.”

In view of the fact that significant majorities of the state’s students fail to perform at grade level in math and English, the Los Angeles Times recently noted, “School districts across California have received billions of dollars to address pandemic learning setbacks—with uncertain results.”

While increased funding has produced little return on investment among school districts in California, a new University of Arkansas study shows that charter schools in cities across the country have delivered real bang for the buck.

Charter schools are publicly funded schools that are independent from school districts, free of many government regulations, and commit to meeting student-outcome goals.

The study calculates the short-term cost-effectiveness and longer-term return on investment and then compares charter schools with regular public schools based on these measurements.

The study authors define cost-effectiveness as points scored on the National Assessment of Educational Progress eighth-grade reading and math exams per $1,000 in funding allocated per pupil.

They define return on investment as the amount students will earn in their lifetimes per dollar invested in their education.

The study looks at data from nine cities: Camden, NJ, Denver, CO, Houston, TX, Indianapolis, IN, Memphis, TN, New Orleans, LA, New York City, NY, San Antonio, TX, and Washington, DC.

According to the study’s cost-effectiveness findings, charter school students scored higher on the NAEP exams “compared to a matched [traditional public school] student, per $1,000 received by their school for their education each year.”

Specifically, the researchers found “that charter schools demonstrate an approximately 40 percent higher level of cost-effectiveness than [traditional public schools] on average across nine cities.”

With regard to return on investment, the study found that if a student attended a regular public school for 13 years, then for every dollar invested in a regular public school there was a $3.94 return on that dollar invested.

In contrast, if a student attended a charter school for 13 years, then for every dollar invested there was a $6.25 return on that dollar invested.

Thus, the study estimates “that attending a charter school for 13 years, compared to a [traditional public school], increases the [return on investment] by 58.4 percent (about $2.30 in additional returns per dollar invested.).”

Crucially, the student demographics at the charter schools in the nine cities were either more challenging or nearly identical to the demographics at their regular public school counterparts.

For example, there were significantly more low-income students at charter schools in Camden, Denver, Houston, and Indianapolis than at the regular public schools in those cities.

The funding difference between charter schools and regular public schools was often stark.

In 2020, regular public schools in Camden received $39,611 per student, while charter schools received about half of that amount–$19,900.

The authors of the study conclude: “Our report suggests that [traditional public school] leaders could learn lessons from charter school operators who have already been operating on much tighter budgets without sacrificing academic quality.”

California policymakers should heed this conclusion and stop making it harder for charter schools to get started and to operate. With less education funding on the horizon, charter schools have much to teach the regular public schools about doing more with less.

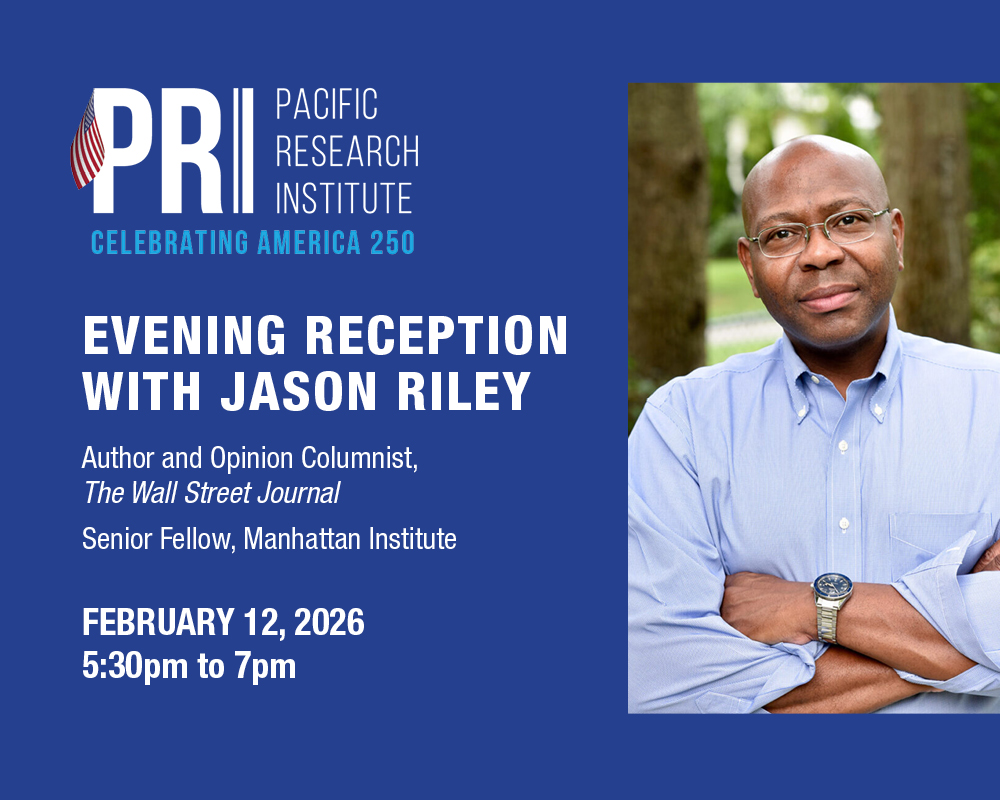

Lance Izumi is senior director of the Center for Education at the Pacific Research Institute. He is the author of the PRI book Choosing Diversity: How Charter Schools Promote Diverse Learning Models and Meet the Diverse Needs of Parents and Children.