May Revise Preview: Sacramento Should Learn Lessons

Wayne Winegarden

May 2024

Governor Newsom is finalizing the May Revision for his 2024-25 budget plan this week. As he does, the parallels between California’s 2009 budget crisis and today’s budget difficulties are too compelling to ignore. Sacramento policymakers should heed the lessons of a now-largely-forgotten budget crisis from 15 years ago to avoid having history repeat itself.

There are clearly some differences – most notably, a nationwide property meltdown has not caused a financial crisis and steep recession. But even here, the differences are too close for comfort. California’s unemployment rate was 5.3 percent in March 2024, the same rate as July 2007 (about 5 months before the 2007-09 recession began.) There are also concerns, even at the Federal Reserve,[1] that the commercial real estate market is in an unsustainable position and poses large financial risks to the economy.

Given these parallels, it would be foolish to ignore the lessons of the 2009 budget crisis. Arguably two of the most important lessons applicable to the current situation are,

- Ultimately, it is income growth that re-establishes fiscal sustainability.

- Budget gimmicks today beget tax increases tomorrow. Making matters worse, even tax increases that are justified as temporary measures to address the crisis inevitably become permanent.

Income Growth, Not Tax Rates, Drives Revenue Growth

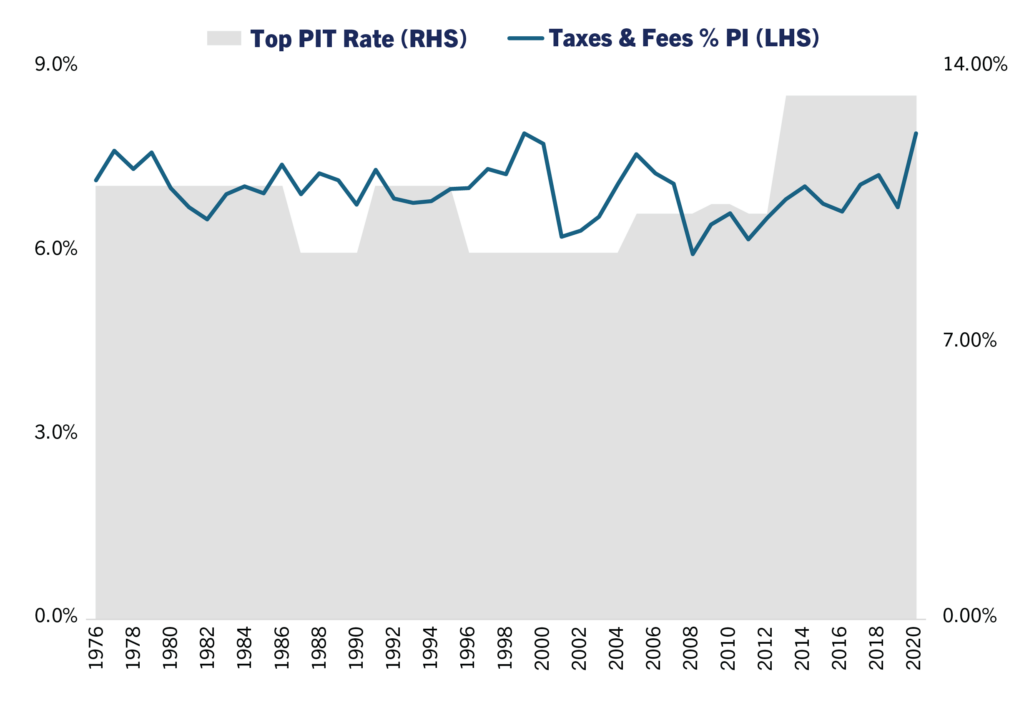

Excluding the distortions created by Covid, total state revenues average 7 percent of personal income, see the blue line in the chart.

Due to California’s steeply progressive tax code, revenues surge during good times. For instance, revenues surged to 7.9 percent of personal income during the peak of the dot com boom in 1999.

Alternatively, when the economy crashes, such as the 2007-09 housing crisis, revenues crater, in this case to 6.0 percent of personal income in 2008. Importantly, the top personal income tax rate was 9.3 percent in 1999 but 10.3 percent in 2008. In other words, higher tax rates do not necessarily raise more revenues or help the state avoid budget crises. Actual revenues raised are intertwined with the health of the economy.

Consequently, policies that delay or dampen growth will prolong a budget crisis. This lesson is particularly important today given the persistent exodus of current Californians, California’s highest unemployment rate in the country,[2] and state’s below average growth in personal income.[3] These data portend continued economic weakness. From a recovery perspective, the current state of California’s economy coupled with the state’s excessively burdensome tax system are a warning against growth-detracting tax increases. California already imposes the highest top personal income tax rate in the country and one of the highest combined state and local sales tax rates.[4] Unfortunately, the 2008-09 budget crisis is a warning that budget gimmicks and delays can increase the likelihood that legislators will turn toward tax increases.

The crisis that culminated in 2009 festered a long time as politicians used budget gimmicks and spending delays in the hope that revenues would rebound. The roots of the crisis are evident in 2006 when the average growth in state revenues fell from double digit growth in 2004 and 2005 to just over 3 percent growth in 2006. Revenue growth slowed further in 2007 to a bit over 2 percent and then declined by a whopping 15 percent in 2008. When coupled with continued brisk spending growth, the result was the 2008-09 budget crisis.

Once the crisis was undeniable, legislators and the Governor could no longer rely on gimmicks or delays. To paraphrase Winston Churchill, having tried everything else, California’s politicians finally turned to actual budget solutions.

These solutions were painful. California needed to implement nearly $60 billion in budget actions. To put this in perspective, $60 billion equaled 60 percent of total tax collections at the time.[5] Closing this gap required two budget packages – in February 2009 and July 2009. The ultimate packages reduced spending by $32.5 billion including cuts to K-12 education and health and social services, increased taxes by $12.5 billion, relied on $8.5 billion in federal stimulus funds (the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, or ARRA), implemented $3.5 billion in one-time revenue measures, and borrowed $2.5 billion. These efforts caused actual declines in year over year spending in excess of 15 percent relative to 2007.

Importantly, the delays and gimmicks that were implemented prior to the February and July budget packages worsened the problem. Between February 2009 and January 2010, credit rating agencies downgraded California’s rating five times, often citing the budget gimmicks and unwillingness to address the fiscal imbalances as the reasons for the downgrade.[6] Lower credit ratings typically increase borrowing costs, which indicates that the $2.5 billion borrowing authorized to address the crisis was ultimate more expensive than necessary.

There are important differences between the current crisis and 2009, however. Most important, relative to personal income, state expenditures impose a much higher burden today compared to 2009. Further, marginal income tax rates are significantly higher today compared to 2009. On the positive side, these data indicate that there are more opportunities for cutting spending today. On the negative side, the already excessive tax rates indicate that there will be more economic damage from proposals that further increase these burdens. Policies that slow California’s income growth will ultimately be counterproductive toward the goal of establishing a fiscally sound state budget.

Applied to the current difficulties, the 2009 budget crisis demonstrates that gimmicks and hope are not a viable plan. Budget crises require difficult decisions. Politicians can delay these decisions, but they cannot avoid them. The sooner those choices are made the better.

[1] Faria e Castro M and Jordan-Wood S “Commercial Real Estate: Where Are the Financial Risks?” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Economic Synopses, November 17, 2023, No. 22, https://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/economic-synopses/2023/11/17/commercial-real-estate-where-are-the-financial-risks.

[2] Preliminary data for March 2024, https://www.bls.gov/web/laus/laumstrk.htm (accessed May 7, 2024).

[3] https://www.bea.gov/news/2024/gross-domestic-product-state-and-personal-income-state-4th-quarter-2023-and-preliminary.

[4] “State and Local Sales Tax Rates, Midyear 2023” The Tax Foundation, July 17, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/state/2023-sales-tax-rates-midyear/.

[5] https://lao.ca.gov/2009/spend_plan/spending_plan_09-10.aspx#:~:text=In%20total%2C%20his%20proposed%20%2441.7,and%20%2410%20billion%20of%20borrowing.

[6] California State Treasurer, https://www.treasurer.ca.gov/ratings/history.asp#:~:text=reaching%20its%20decision.-,July%202009,to%20its%20severe%20fiscal%20crisis.