Many cities are zoning people out of their homes

By Wayne Winegarden

A growing housing unaffordability problem is now plaguing cities across the country. The roots of this crisis are errant monetary and fiscal policies that, before they stoked our current bout of inflation, incentivized a surge in housing prices. A national housing affordability problem did not arise in many cities immediately, however, due to the historically low interest rates.

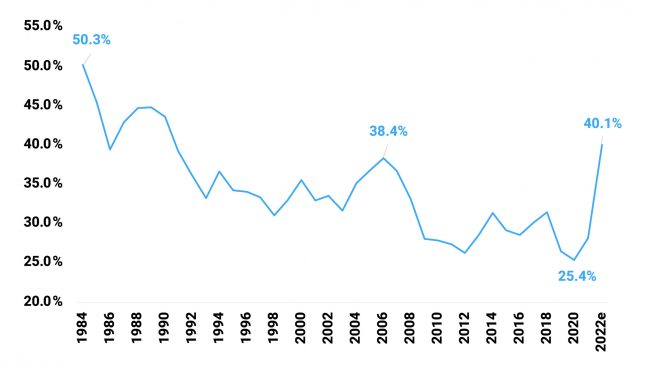

The resurgence of inflation caused a spike in interest rates, which changed everything. Rising interest rates coupled with the high house prices is now driving the national affordability crisis. Figure 1 visualizes the extent of the current housing affordability problem.

Figure 1 estimates the costs of financing the median priced home at the prevailing 30-year fixed mortgage rate relative to the median household income between 1984 and 2022. Figure 1 demonstrates that, in 1984 as the economy was recovering from the previous bout of inflation, housing was incredibly unaffordable. Back in 1984, the costs of financing 100 percent of the median priced home at the prevailing 30-year fixed mortgage rate would have equaled more than one-half of the median household’s income.

In a positive trend for families, housing affordability generally improved over the next quarter century due to a combination of rising incomes and declining interest rates – with an interruption caused by the 2007 housing bubble. However, the speed and scale of the reversal in housing affordability is evident by the near vertical increase in the housing affordability index (e.g., indicating a huge decrease in housing affordability) that has occurred this year. Nationally, housing has not been this unaffordable since the mid-1980s.

Of course, housing is an inherently local issue and the affordability trends in specific cities will vary from this national average. And distressingly, many western cities, especially in California, have been suffering from an unaffordable housing landscape even before the national crisis.

And the reason is simple: local zoning laws. Understanding this connection, while always important, is imperative given the national unaffordability problem.

Ostensibly, cities promulgate zoning regulations to ensure safety and maintain the sustainability of the local environment. These ordinances are also supposed to maintain compatibility among adjacent land uses to ensure that toxic chemical dumps are not located in the middle of residential neighborhoods.

While the goals are laudable, too many cities impose excessively burdensome zoning regulations that inflate the costs of construction and, in extreme cases such as Los Angeles, severely diminish the ability of builders to construct new homes.

In fact, as Steven Greenhut argued in a December 7th PRI blog post, unaffordable housing is not an issue of insufficient developable land as many anti-growth advocates might claim. The U.S. has plenty of developable land. The issue is that local governments prohibit responsible housing development. The lack of development inevitably leads to supply constraints relative to local demand, and the resulting shortages create the crushing housing affordability problems.

Vanessa Calder of the Cato Institute directly linked the adverse impact from zoning regulations on housing affordability in 2017 arguing that:

(T)he regulations complicate or prohibit housing development, which reduces supply. Basic economic theory suggests that if demand is rising, then housing prices will increase the most in cities where supply is the most constrained by such regulations. Empirical research across U.S. cities suggests that, indeed, zoning rules reduce supply, which in turn increases prices.

The first step toward demonstrating this connection is finding an accurate measure of the stringency of these ordinances across cities, which is difficult given the inherently subjective nature of zoning regulations. One excellent source is the Wharton Residential Land Use Regulatory Index, which is based on a 2018 nationwide survey of residential land use regulation in 2,450 communities. The index is designed to capture the stringency of the local regulatory environments. Based on the response rate, the index was able to rate 44 metropolitan areas, 24 of which are among the top 50 largest cities in the country.

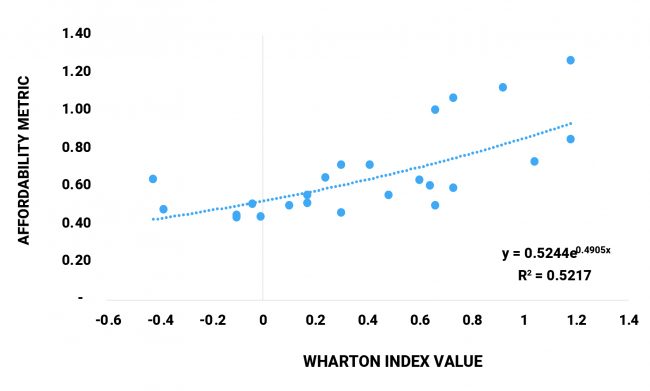

Focusing on these 24 cities, the affordability metric was estimated using the most recent local income and housing price data and the current rate for a 30-year fixed mortgage. Comparing these affordability metrics to the Wharton index reveals that those cities that are imposing more restrictive zoning regulations have much worse affordability problems. See Figure 2.

Each dot in Figure 2 represents a city. Each city’s ranking in the Wharton Land Use Regulatory Index is measured along the x-axis – the higher the number, the more stringent the city’s zoning regulations. The median housing affordability level for each city is measured along the y-axis – the higher the affordability score, the less affordable housing is in that city. The dots in Figure 2 demonstrate a clear positive relationship – those cities with more stringent zoning regulations have less affordable housing.

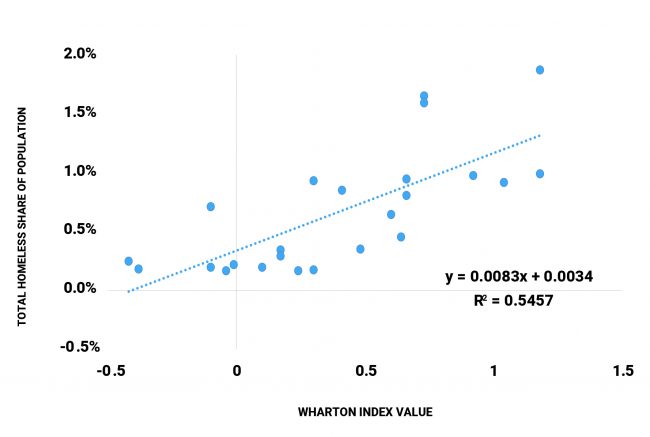

Unfortunately, the adverse impacts from excessive zoning regulations goes beyond unnecessarily expensive housing. When zoning regulations make housing less affordable, they also worsen the problems of homelessness, which is demonstrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3 provides the same comparison as Figure 2, except instead of comparing housing affordability in each city to the stringency of its zoning regulations, Figure 3 compares the relative size of each city’s homelessness population. The clear positive relationship demonstrated in the figure should not be surprising – when cities make housing less affordable, it puts vulnerable people at greater risk of becoming homeless. And, while mental illness and drug addiction are important drivers of the homelessness problem, Figure 3 suggests that zoning regulations that make housing less affordable is a driver as well.

In light of these impacts, the path forward is clear: cities should eliminate the housing supply barriers created by zoning regulations to achieve the goal of a more affordable housing environment. These reforms should include deregulations that allow more multi-family structures, reduce the red tape for obtaining approvals for new construction, and open more land for development.

Reducing these barriers will incentivize greater housing development, increase the supply of housing, and directly alleviate the shortages that commonly plague the least affordable cities. The result will be a more affordable housing landscape.

Wayne Winegarden, Ph.D. is a Sr. Fellow and Director of the Center for Medical Economics and Innovation at the Pacific Research Institute