Lessons from Africa: Private utilities offer a way forward

By Scott Beyer | February 2, 2024

I was exploring a rural Kenyan village last spring when noticing an infrastructure dichotomy – one I later realized is characteristic of Africa. The government in Wamunyu, a farm town two hours from Nairobi, provided people there nothing – no electricity, clean water, paved roads, sewage, etc. People were carrying large stick bundles on their backs, which, my driver explained, they rubbed together to create fires and boil water. “And yet,” he explained, “they still post on Facebook.”

The dichotomy, I later realized, is between the nature of public and private provision. Utilities across Africa that are generally managed by government agencies or through public-private partnerships are spotty. The utilities that have been opened to private competition grow increasingly available, even for those without money to buy much else. The contrast should be acknowledged by African authorities and set the direction for future provision.

State failure in utility provision

Continent-wide, electricity is scarce – something I learned firsthand while visiting nine sub-Saharan African countries during a recent 1.5-year Global South trip. At current expansion rates in central and western Africa, reports the World Bank, “263 million people in the region will be left without electricity in 10 years.” Where power exists, providers keep the lights flickering on and off in what amounts to a daily struggle. South Africa is a particularly notorious example.

Many parts of the country endure “load shedding” blackouts to manage available power. This typically happens three times a day, but in major cities can occur a dozen times daily. The result is lower economic growth, increased car crashes (from non-working traffic lights), and revenue loss for businesses.

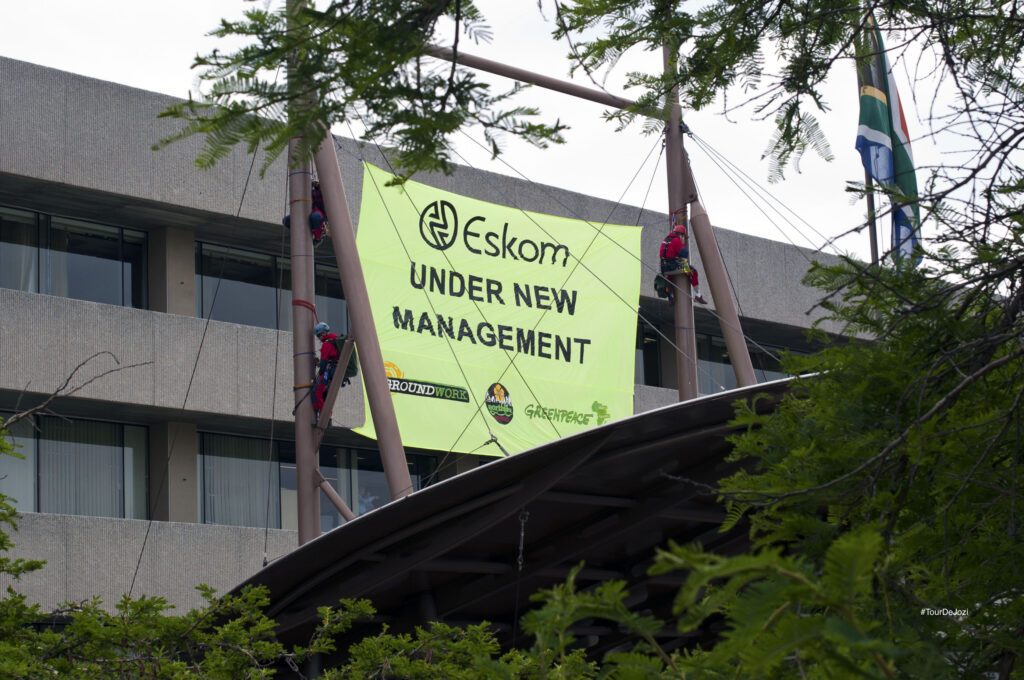

Eskom, the country’s state-owned electricity provider, supplies the overwhelming majority of South Africa’s power. It can’t afford to expand capacity as it is $23.5 billion in debt. Eskom has a history of corruption and mismanagement, with employees looting the treasury. And the South African government has blocked competition, for example from upstart green energy suppliers. Other African power providers follow this top-down model, with similar results.

Much of Africa also lacks clean water. “On average across 34 African countries, about half (49%) of citizens went without enough clean water for home use,” notes Afrobarometer. In fact, the situation worsened in the 2010s across the surveyed countries.

As with electricity, corruption and poor governance are a problem. Water rights are often traded through bribery and crony public-private deals. Such an arrangement between the Tanzanian government and a provider led to mass water pollution. The watchdog organization Transparency International claims that unethical water arrangements make water access per household 30% more expensive. Revenue mismanagement means that damaged old infrastructure isn’t repaired.

Waste management, typically a local government responsibility, is also a problem. Many Africans don’t enjoy central sewer systems as we are accustomed to in America. Neighborhoods don’t have commodes that usher waste to septic systems or treatment plants.

Instead, people use a mix of electricity-free outhouses (such as in the rural Kenyan village) or just go in natural water bodies that others use for bathing and drinking. This is due either to a lack of standard municipal waste collection authorities or the presence of poorly managed ones. In total, just 55% of municipal solid waste is removed, per United Nations statistics.

Telecom: A case study of private success

Then it comes to internet access. Currently, 570 million Africans, or just under half the continental population, have it. Three-quarters of Africans should gain access by 2030. This growth includes an aggressive fiberoptic rollout by Google, Meta and others. But much of it is thanks to satellite deployment.

Providers like Eutelsat and Starlink have expanded (and Starlink only started business in Africa in 2023) without deploying expensive fixed infrastructure, which often doesn’t pencil in sparse areas (also a common barrier to internet access in the rural United States.).

Further capacity expansions are ahead. 5G reach is growing, and countries like Rwanda and Burkina Faso have improved internet speeds through increased fiber rollout. Rwanda’s market is competitive, with 114 providers authorized to operate, causing it to jump nearly 50 spots on the worldwide broadband speed index.

This, too, can take on a public-private dimension. Burkina Faso’s expansion was done in participation with the Chinese company Huawei and financed by Bank of China. But there is still an open, competitive market thriving around these deals.

Equally important is the proliferation of phones and mobile internet plans. Abundant discount smartphones – called “smart-feature phones” – can be purchased in Africa for as low as $20. International firms from China, India and Europe offer their own models, in a competitive process that drives prices down. Around 50% of Africans now use cell phones.

Internet use can still burden low-income Africans, so providers reach consumers through “pay as you go” plans. Here, too, the market is competitive, with a plethora of providers, both from within Africa and from overseas companies, such as India-based Airtel. Typically, people buy new data plans weekly. These providers also offer banking and insurance.

As a result, half of Africans have a 4G connection and 75% have 3G capability. Mobile apps like Messenger and WhatsApp allow communication free of additional charge. This will help Africans join the digital economy and build wealth.

Another area where market dynamism shines in Africa is mass transit. As I noted in a previous Free Cities Center piece, major African cities have complex jitney bus and motorbike networks. Owned and driven by sole properties (albeit with varying degrees of central management from cartels and government agencies), such cheap transport improves mobility for residents, most of whom can’t afford cars. Again, this is an organic private-sector response to African governments that fail to provide reliable transit.

The dichotomy, then, lies here: Africa’s publicly run utilities show the public-choice flaws innate to government management. At best, they provide services poorly; at worst they become organized political blocs that block competition. Africa’s market-driven utilities show how the private sector rises to serve needs going unmet by government.

The answer, in a region where even privatization under government oversight often doesn’t work, is true market liberalization. Open traditionally government responsibilities to any and all private entrants. If it has worked for telecom, consider what it might do for water, sewer, electricity and other provisions that average Africans now lack.

Scott Beyer owns Market Urbanism and is author of the Free Cities Center book, “Latin America’s Urban Experience: How markets help developing countries cope with government dysfunction.”