Proponents of housing first claim that housing is a basic human right, and a permanent and stable home is the best platform from which to help people overcome the challenges that led to their homelessness, including the problems of mental illness and addiction.

As a result of this premise, the organizations pursuing housing-first strategies try to place a person experiencing homelessness in a home as quickly as possible, without any preconditions such as sobriety or imposing any program-participation requirements.

Seattle has been implementing such policies since the early 2000s when it authorized a new regional homelessness authority that explicitly required the use of “evidence-based, housing first” policies.

Portland also is a long-time advocate of housing first. It authorized $258 million in borrowing in 2016 with the goal of investing these resources into building more affordable housing. In May 2020, voters also approved tax increases (Measure 26-210) with the goal of providing $250 million in revenues dedicated toward helping homeless people find and remain in homes – regardless of their addiction and mental-health problems.

In California, the view that housing is a necessary precursor to treatment began with the passage of Senate Bill 1380 in 2016. The law codified “housing first” as the official policy of the state. In the same year, Los Angeles voters passed Proposition HHH, which authorized the city to issue $1.2 billion in bonds to support the construction of permanent housing for homeless people.

Proponents claim that the empirical evidence support the housing-first framework. For example, an influential 2009 JAMA study found that a housing first program decreased the costs associated with homelessness after six months and retained people in housing for a longer period. There are reasons to be skeptical of these results, however.

Diving into the weeds briefly, the JAMA study measured the program’s ability to reduce costs relative to the homeless people who were unable to enroll in the program – the control group or “wait listed” cohort. But there were meaningful differences between those on the wait list and those who received housing first services that likely affected the results. For instance,

- The wait listed group was more likely to have some college education but much less likely to have graduated college or earned an advanced degree.

- The people who entered the housing first program had experienced a larger number of “stable housing periods” (50 percent more) since first becoming homeless compared to the wait-listed group.

- The results for the wait-listed group were measured at different time periods compared to the housing first group.

Having different education levels or a history of more stable housing clearly will affect whether an intervention is successful or not, but the authors simply do not know how these differences influenced their results. These types of methodological obstacles are not unique to the JAMA study, either.

Overlooking the potential for methodological problems, the evidence that an exclusive housing first approach can address the root causes driving the homelessness problem is still scant. As a 2022 article in the Portland Tribune noted:

“While dozens of studies found higher long-term housing stability in housing first programs, they also found no measurable changes in mental health, addiction, income, or employment outcomes compared with the usual social services. More importantly, there is no evidence showing a housing first approach does anything to reduce the overall number of homeless in a community.”

The article summarize that “housing first places people in taxpayer-funded housing with enormous costs for construction, operations, and so-called wrap-around services, while not solving the underlying issues that led people to the streets in the first place.” Put simply, the evidence demonstrates that the housing first approach does not achieve its goal of reducing homelessness, let alone eliminating it.

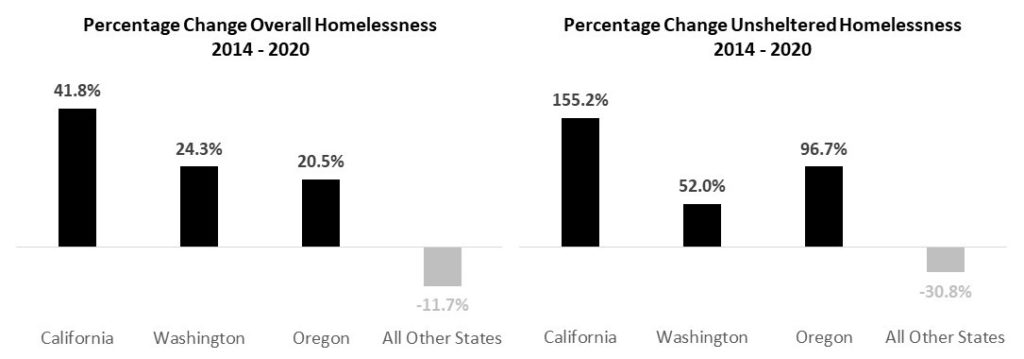

The homeless data maintained by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development confirm these trends. Using data through 2020 (because the impacts from the Covid-19 pandemic prevented HUD from measuring the unsheltered homeless in 2021), the decline in the number of homeless and the number of unsheltered homeless ended in 2014 for California and Oregon, and in 2013 for Washington.

Starting in 2014 and lasting through 2020, the three West Coast states that heavily rely on the housing first approach have seen a surging homelessness problem, which are most acute in the large cities of Los Angeles, San Francisco, Portland and Seattle.

Consider that these increases occurred during a period when there was no national increase in the homelessness population – in fact, the homeless population declined overall in the rest of the country. Since the homelessness problem worsened in these states while it was lessening in the rest of the country, the efficacy of an exclusive housing first policy focus is, at a bare minimum, questionable.

Source: Author calculations based on HUD data

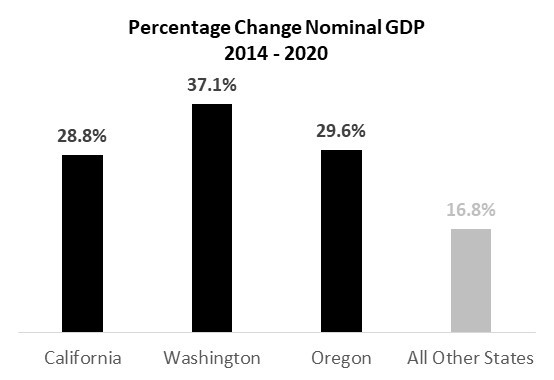

The failure of housing first is starker once the relatively stronger rates of economic growth in California, Washington and Oregon are considered. Unadjusted for inflation, the size of California’s, Washington’s, and Oregon’s economies were 28.8 percent larger, 37.1 percent larger, and 29.6 percent larger in 2020 compared to 2014, respectively. These growth rates were all significantly higher than the growth in the economies of the remaining 47 states (16.8 percent). Since a growing economy should reduce the numbers of homeless people, the growth in the homeless populations in these states relative to the decline in homelessness in the remaining states raises further questions regarding housing first’s effectiveness.

Source: Author calculations based on BEA data

Making matters worse, not only is housing first ineffective, but it is also costly. As the controller of Los Angeles noted in his audit of Prop HHH, the “projected per-unit costs remain high. The median cost of building these units ($531,373) approaches – and in many cases, exceeds – the median sale price of a condominium in the city of Los Angeles ($546,000) and a single-family home in Los Angeles County ($627,690).”

Over the past three years, California has spent more than $13 billion dollars to address homelessness, roughly $30,000 annually for every homeless person in the state, all in support of a strategy that has dubious underpinnings. Yet, California’s homelessness programs are disjointed, ineffective and poorly managed, according to the state auditor’s office.

Eye-popping costs and bureaucratic snafus are endemic to a housing first approach. They are also reflective of the restrictive zoning laws and regulatory burdens that drive up the cost to build any housing in these states and severely restrict their supply – an issue most pronounced in urban areas where homelessness has reached epic proportions.

These regulations are an important driver of the housing affordability problem that, along with issues of addiction and mental illness, are forcing too many people on to the streets in California, Oregon and Washington. Although homelessness isn’t solely a housing issue, it is counterproductive for governments to attempt to build housing for every homeless person without dealing with the myriad governmental impediments to building it.

Homelessness is caused by a combination of economic, health and addiction considerations. This does not mean that transitioning some homeless people into immediate housing is not a potentially good option for some people. But for many others, it will require shelters and effective health facilities first and, only then, will sustainable housing be possible. Homelessness is a complex problem that requires diverse solutions.

As a Cicero Institute study noted, housing first has failed in part because it “appears to attract more people from outside the homeless system, or keeps them in the homelessness system, because they are drawn to the promise of a permanent and usually rent-free room.”

Western cities can’t possibly build enough housing for the homeless – often at costs that exceed $700,000 a unit – without resolving the underlying financial and regulatory issues that make housing construction so difficult. They need to address the social problems that have caused so many people to be on the streets in the first place.

Wayne Winegarden is senior fellow in business and economics at the Pacific Research Institute, as well as the director of PRI’s Center for Medical Economics and Innovation.