Growing federal debt will take its toll on city budgets

John Seiler | December 20, 2024

IT HAS TO END SOMETIME. The national debt has soared above $36 trillion – and counting. And when the party does end, cities are going to be hit. How hard is for the future. The key is the yearly interest payments, which the U.S. Treasury Department’s October report estimated will hit a record $1.2 trillion for fiscal year 2025, which ends next Sept. 30.

The Federal Reserve Board’s Nov. 7 interest-rate cut by one-quarter percentage point could reduce that somewhat. Except the Congressional Budget Office projects the budget deficit will slam at $1.9 trillion in 2025 and $1.8 trillion in 2026 and 2027, followed by similar or higher deficits the next seven years.

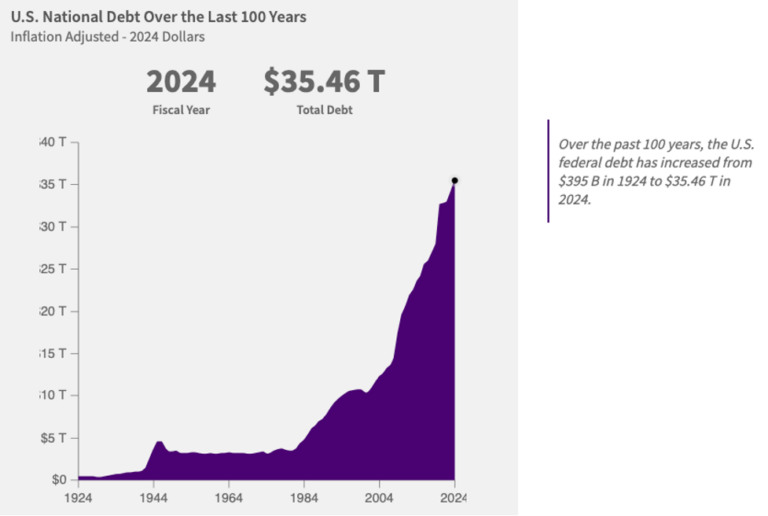

Here’s the U.S. Treasury Department’s most recent chart of the debt, as of September 2023:

Note the huge surge in debt that occurred beginning in the early 2000s under Republican President George W. Bush, with the bipartisan splurging continuing under Barack Obama, Donald Trump and Joe Biden. Trump and Biden each boosted the debt by $8 trillion.

We don’t know when Congress finally will have to start cutting back the wild spending. But in 39 dense pages the Treasury document lists some of the current direct assistance mainly to cities and counties, the amounts for fiscal 2024:

- $1.7 billion for law enforcement assistance;

- $21.7 billion for aid to local airports;

- $26.8 billion for tenant-based rental assistance;

- $12.9 billion for community planning and development.

An August 2024 Urban Institute study calculated overall federal revenue transfers to California, combining state and local receipts, was $3,670 per capita. That amounted to 22.7% of the $16,114 per capita the state itself garnered from state and local revenues.

What if nothing is done? “The federal government has been handling the deficit by selling more treasury securities,” Raymond Sfeir told me; he’s the director of the A. Gary Anderson Center for Economic Research at Chapman University in Orange, Calif. “So, if they do not decide to make cuts, not just to states and local governments, but in other components of the budget, the deficit will grow bigger.”

What will happen when cuts finally must be made? Will the federal government cut its funding of city, county and school programs? “That is certainly one possibility,” Sfeir said. “I have not seen a plan coming from Washington to address the interest-payment problem.” However, “Investment by the federal government on highways, bridges and schools will suffer. Keeping the same Social Security taxes, benefits and retirement age would no longer be an option either. Percentage-wise, all components of the budget will have to be pushed down.”

How will the local governments deal with the federal government’s fiscal irresponsibility? He said the federal COVID funds already have been spent, and cities now are trying to cut down on expenses. Some might try to increase taxes.

Indeed, I titled in my Dec. 6 Free Cities article, “Voters slam California with new local taxes and bonds.” The school bonds require a 55% approval margin, general-purpose sales tax increases only majority approval and special-purpose sales tax increases two-thirds approval. The school bonds are paid for by increased property taxes…. Of 533 local tax and bond/tax measures statewide, 405 passed and 128 failed, a 76% passage rate. That’s actually higher than in recent elections.”

Some details: “Voters slammed local taxpayers with around $2.3 billion in new direct tax increases and $47.1 billion in new bond debt, which I call ‘bonds/taxes’ because bonds are repaid with increased tax rates.” A California City Finance tally of similar local ballot measures on the March 5 ballot found: 83% of city general taxes passed (majority vote required), 57% of city special taxes or bonds passed (two-thirds required) and 60% of school bonds passed (55% required).

The voting results mean that when the inevitable federal budget cuts come in future years local governments certainly will be tapping the taxpayers again, at least in California and other liberal states. And voters likely will go along with it.

On the positive side, Proposition 5 lost, 55% to 45%. It would have reduced from two-thirds to 55% the threshold for passing local bond measures to fund housing and infrastructure, making them easier to pass. But that close margin means the tax-increasers likely will try again, perhaps in 2026. It also was an attack on California’s venerable Proposition 13, which in 1978 established the two-thirds threshold. Pepperdine University economics professor Gary Galles warned Prop. 5 was especially pernicious because, while supposedly funding only “infrastructure,” its wording was so vague it could have been used for anything.

Then there’s how the states will respond to federal cuts. A precedent was the response to the Great Recession that struck in 2007-08. In December 2012 the Brookings Institution released a study, “State and Local Budgets and the Great Recession.” It noted the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 “directed unprecedented fiscal relief to states and localities.” However, as seen chart at the beginning of this article, the federal debt was “only” $14 trillion in 2008, or 40% of today’s total.

The study found even the federal largesse beginning in 2008 “did not offset state and local revenue losses and the stimulus programs have now expired.” And any federal aid to state and local governments likely would be cut as part of “any long term federal deficit reduction package.” That 2012 analysis came when the debt was $21 trillion, or 60% of today’s amount.

With Donald Trump’s election as president, the new Department of Government Efficiency, headed by Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy, might cut spending now going to local governments. That also would prompt calls for local tax increases.

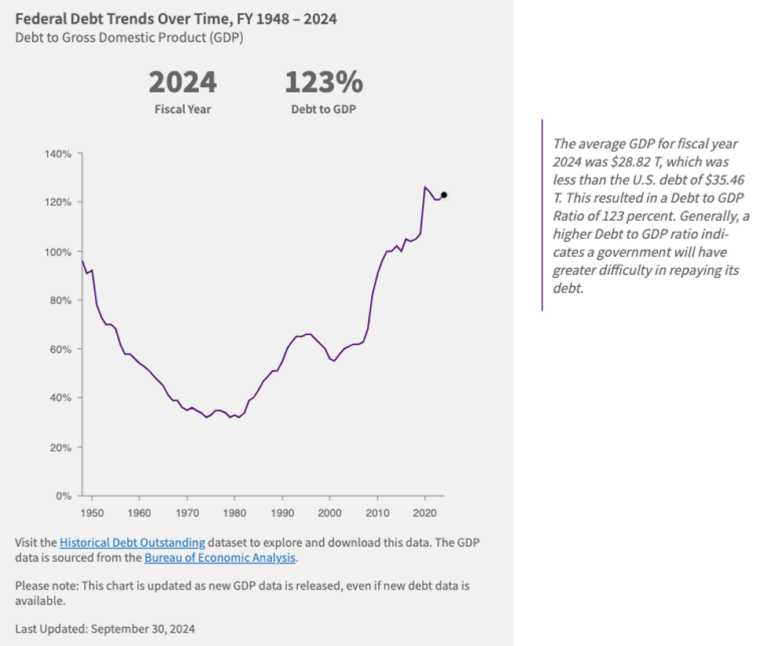

Finally, the data so far does not take into account inflation. The best way to do so is to show the percentage of federal debt to GDP. Here’s the Treasury’s chart:

The conclusion is inevitable: One way or another, the interest payments on the national debt will force reduced spending in other areas. With Social Security, Medicare, defense and other priorities standing above aid to state and local governments, the latter will be hit. They will have to make up the difference with tax increases or service cuts.

John Seiler is on the Editorial Board of the Southern California News Group.