Nitrogen is the plant equivalent of parents telling their children to eat their vegetables.

In kids, vegetables provide micronutrients needed for proper growth, fiber, and energy. In plants, nitrogen provides similar benefits, ensuring plants have the needed energy to grow to the best maturity and provide the most crop at the right time.

In 2018, the State Water Resources Control Board gathered a group of experts in the areas of agriculture, environmental justice, the broader scientific community, regional water boards, and various public agencies to create Order WQ 2018-0002 to monitor nitrogen in the water supply.

Under the auspices of the order, which was revised and newly approved in September, there are two steps to complete annually for successful nitrogen monitoring. Growers must first report “the pounds of nitrogen applied, and the pounds of nitrogen removed for each field annually on a per acre basis” to their regional water board. Once the ratio of nitrogen in versus nitrogen out is determined, growers must then address any multi-year upward trends in the ratio that are recorded.

Tracking historic nitrogen use data has other benefits for both regional water boards and growers, too. It helps agencies and growers work together to find solutions that are mutually beneficial for keeping growers productive and public water sources minimally impacted by nitrogen intrusion.

Yet, for activist groups, annual monitoring of nitrogen levels in water is not enough. A lawsuit was recently filed asking the State Water Resources Control Board to reinstate Agricultural Order 4.0 as passed by the Central Coast Water Board earlier this year and revoked by the state board.

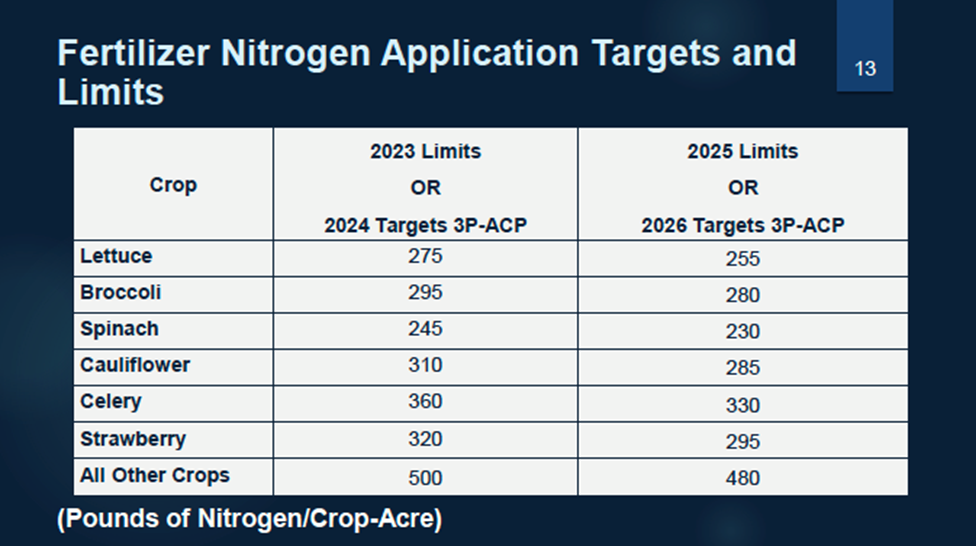

There are some fundamental issues with Ag Order 4.0, however. Namely the nitrate limitations for various crops and the phasing in of ever-more restrictive nitrogen application levels in subsequent years. Below is a page from a 2021 workshop discussing Ag Order 4.0, specifically the application targets and limits imposed for specific crops grown throughout California now and, likely, into the future.

The targeted limits for 2023 are slightly less concerning than the targets in the 2025 column. Specifically, the 2023 limits are already being met by most growers throughout California.

Looking ahead to the 2025 proposed limits, the numbers are harder to achieve given the plants that are identified in the chart. The California Department of Food and Agriculture have an excellent chart of crop fertilization guidelines that includes almost all of the crops listed in the Ag Order 4.0 chart shown above. The guidelines outline minimum and maximum nitrogen application needs for each crop and when application is needed as well as how much is needed for a spring/summer or fall/winter planting.

As an example, using the information from CDFA, celery requires 20-30 pounds of nitrogen per acre either pre-planting or at planting. After planting, nitrogen needs vary dramatically based on the soil. In parts of California’s Central Coast, no additional nitrogen may be needed, based on residual soil nitrogen levels or up to 400 pounds of nitrogen per acre may be needed for winter-planted celery in well-draining soil. If a total of 430 pounds of nitrogen per acre was applied, the grower would be well outside the limits of both the 2023 and 2025 – 360 lbs/ac and 330 lbs/ac respectively – set by the Ag Order 4.0.

The most detrimental component of these proposed limitations is that they are set for an entire year. However, many farms in the Central Coast region are double-cropped – or planted twice – meaning these proposed limits would be exceeded almost without fail annually.

No one is discounting the need for monitoring of nitrogen levels in municipal water supplies. High nitrogen levels are dangerous for everyone – farmers and ranchers included – however, taking away the ability of food producers to do their jobs, provide for their communities, and continue to employ a great many people by limiting the yields of crops in the area is not the answer either.

Proper monitoring of the nitrogen levels in the water, mitigation activities that allow agriculture and communities to work together toward mutually beneficial, science-based solutions, and stakeholder engagement are all pieces of the same puzzle. Agricultural and non-agricultural interests can work together when both sides come to the table willing to work. Filing a lawsuit to force action that potentially causes harm to one side or the other, is not the cooperative spirit needed to find a solution to the problems on the Central Coast.

Pam Lewison is a farmer in Eastern Washington. She is also the Agriculture Research Director for the Washington Policy Center and a contributor to Pacific Research Institute.