The New York Times has a summary of the Biden Tax Plan claiming to explain “some of the main provisions included in the plan and how they’re intended to work.” While the Times may have accurately explained how the Administration “intends” for the tax hike to work, these intentions are simply inconsistent with the historical experience.

The justification for the tax increases, as the Times puts it, is to put the corporate income tax rate “more in line with global peers”. This assertion is then justified by comparing the U.S. to the other OECD countries (an international organization with 37 member countries) based on each country’s corporate income tax revenues relative to the size of the economy (measured as GDP).

The amount of tax revenue raised relative to GDP is not the same thing as the corporate income tax rate.

Corporate income tax revenues relative to the size of a country’s GDP will vary for many reasons. How profitable are companies in the country? How broad is the corporate income tax base? How do firms structure themselves? All of these questions will impact the corporate tax revenues share of GDP in addition to the actual tax rate that is levied.

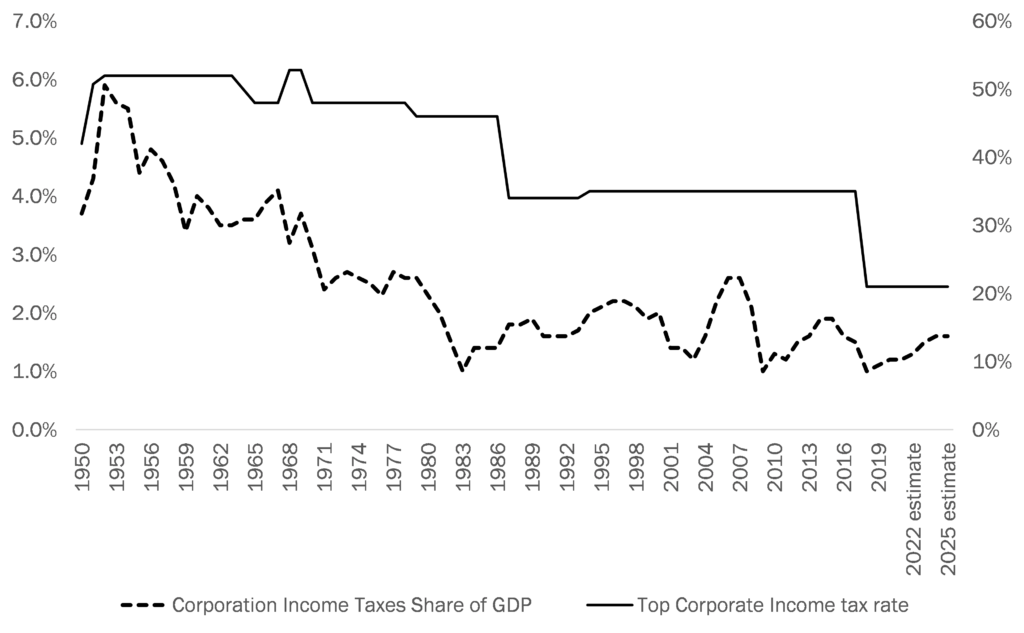

Perhaps more troubling, these claims obscure the long run trends in U.S. corporate income taxation. To visualize the long run trends, Figure 1 below compares U.S. corporate income tax revenues relative to the size of the economy and the top corporate income tax rate.

When the proponents of the Biden Administration’s tax hike claim that corporate income tax revenues used to be higher relative to the size of the economy, they are correct. But, the data also show that corporate income tax revenues relative to GDP experienced a long-term decline that began in 1952 and lasted until 1983. This decline had nothing to do with reductions in the top corporate income tax rate, which hovered around 50 percent during this entire period.

Perhaps even more important for the debate today, the long-term decline ended around the time of the 1986 tax reform. Further, the significant corporate income tax reductions in 1986 and 2017 did not lead to a resumption of the decline. Instead, the size of corporate income tax revenues relative to the economy have vacillated around 1 percent to 2 percent level since the 1986 reform.

Figure 1

Corporate Income Tax Revenues Relative to the Size of GDP (LHS)

Compared to Top Corporate Income Tax Rate (RHS)

1950 – 2019

2020 – 2025 estimate

Source: OMB and Tax Foundation

Source: OMB and Tax Foundation

As for actual tax rates, the Tax Foundation summarized the relevant comparison:

Declines have been seen in every major region of the world, including in the largest economies. The 2017 tax reform in the United States brought the statutory corporate income tax rate from among the highest in the world closer to the middle of the distribution. Whereas in 2017 the United States had the fourth highest corporate income tax rate in the world, it now ranks towards the middle of the countries and tax jurisdictions surveyed.

Justifying an increase in the U.S. corporate income tax rate in order to make the U.S. “in line with global peers” is, consequently, factually incorrect. The U.S. is already in line with global peers, and any increase will make the U.S. a high-tax destination once again.

The historical record is also not supportive of a major long-term revenue gain from the hikes. Unfortunately, once the Biden Administration ensconces the new spending programs, the revenue shortfalls will likely encourage politicians to argue for more tax increases, which will need to include families making less than $400,000, rather than the more appropriate spending cuts.

Wayne Winegarden is senior fellow in business and economics at the Pacific Research Institute and director of PRI’s Center for Medical Economics and Innovation.