A More Effective Safety Net, Not A Basic Income, Will Help Lift People Out of Poverty

Wayne Winegarden and Nikhil Agarwal

December 2024

2024 was a good year for proponents of a universal basic income (UBI). Following the 2019 experiment in Stockton, UBI pilot programs are underway across cities in California including Fresno and Sacramento. This is unfortunate.

Advocates such as former Stockton Mayor Michael Tubbs argue that “we need a social safety net that goes beyond conditional benefits tied to employment, works for everyone and begins to address the call for racial and economic justice through a guaranteed income”. A UBI allegedly fills this gap by providing income security, encouraging work, and improving low-income families’ quality of life.

These benefits are merely speculative and are not realized in practice.

First, going from pilot to policy raises important scalability and cost questions that undermine the feasibility of a UBI. Second, as Tim Anaya explains, even former Mayor Tubbs’ Stockton experiment does not demonstrate the efficacy of a UBI. The pilot program’s design was so flawed that how recipients spent the money and whether it improved their long-term financial stability is simply unknown.

Third, contrary to proponents’ assertions, a UBI disincentivizes work. Researchers at the University of Toronto, for instance, found UBI programs discouraged work and reduced people’s non-subsidized income. By discouraging work, UBI programs eliminate opportunities for low-income workers to gain valuable skills and decrease their long-run earnings potential. In other words, UBI programs create a poverty trap [link to benefits cliff piece] just like the current income support system.

Also noteworthy, UBI proponents aren’t advocating for a basic income that is universal. Making it universal would mean that California would need to tax Larry Ellison (net worth as of October 2024 of $175 billion) to provide a monthly income to Mark Zuckerberg (net worth as of October 2024 of $181 billion). And vice versa. Such a transfer system makes no sense. It also makes no sense to tax the family earning $300,000 a year to provide a basic income to a family earning $299,000 annually.

In other words, proponents are using the UBI concept to simply expand on the litany of programs that already exist.[1] But California already spends a tremendous amount of money funding these programs. According to the U.S. Census, total state and local spending on public welfare (including federal funds) was $190.6 billion in 2022. This is an incredible sum. It means that, per capita, California spends $4,890. Per person in poverty, the state spends $31,753 – or around $90,000 per family of three living in poverty![2]

One would hope that spending $90,000 per poor family would be sufficient to not simply alleviate the hardships of poverty but to help lift families out of it. Yet, this has not been the case. The supplemental poverty rate in California remains excessively high (15.4 percent) even though the U.S. economy has continued to grow around 2.5 percent for the past two years. These results demonstrate that, if the goal is to lift people out of poverty rather than alleviate its hardships, California’s current approach is failing.

As we have argued in previous PRI pieces, the fundamental concept of basic income isn’t necessarily wrong if reforms replace the currently overly complex array of programs with a simplified cash-based system. A properly designed cash-based system that includes work and education requirements would be more effective, cost less, and eliminate many of the disincentives that plague the current system.

Take the negative income tax (NIT) proposal by Milton Friedman in 1962. The premise of the NIT was simple – what poor people need is money. Therefore, replacing all the in-kind benefit programs with a cash-based system provides lower income families with the resources they need while reducing government administrative costs and empowering individuals to decide for themselves how their benefits would be spent. Importantly, a cash-based system makes it easier to phase out income support benefits at a constant rate, avoiding many poverty trap problems.

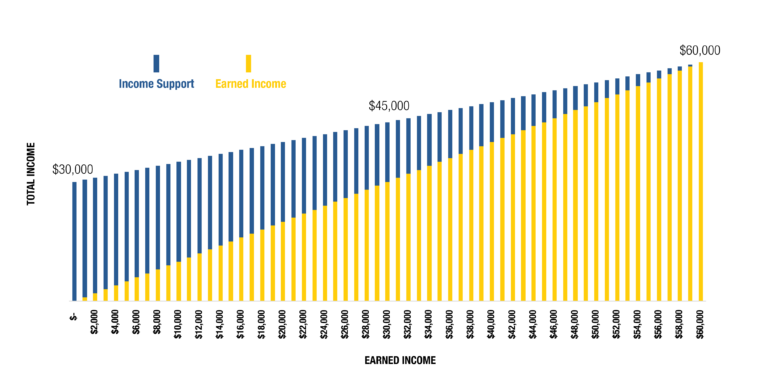

Given the high level of current spending, the current complex and ineffective income support programs can be replaced with a generous cash-based income support system while still saving money. The figure below traces out the benefits for a cash-based income support system that guarantees California families an income of $30,000.

In this example, the income support would decline by 50-cents for every dollar the family earns until an annual income of $60,000 is reached. At this level of income, the support payments would completely phase out. However, since families are continually better off from working or gaining additional skills, the cash-based support system moderates the poverty trap disincentives that pervade the current system.

Based on the current income distribution and the number of households currently in California, this proposed income support program would cost between $60 billion and $70 billion – well below the 2022 expenditures of $190.6 billion. This leaves plenty of revenue to adjust the size and coverage of the support payments, account for differences in family size, health needs, and other considerations while still reducing overall state spending.

The growing UBI experiments across California are disconcerting due to the program’s well documented flaws. While layering a UBI onto the current income public assistance programs is troubling, replacing the current system with a simplified cash-based system is worth exploring. Such a system, which should include job search and education requirements, would cost less, simplify programmatic administration, help the needy more efficiently, and encourage work and economic advancement.

[1] These programs include: CalFresh, Low-Income Heating Assistance Program, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, Earned Income Tax Credit, Supplemental Security Income, free breakfast/lunch programs, Medi-Cal (Medicaid), and housing assistance programs.

[2] The supplemental poverty rate is used for these calculations to account for California’s higher cost of living.