Last week the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) published its latest fiscal outlook for California. The headlines were so great that you could almost hear the champagne corks popping in Sacramento.

Not only has the state budget in California run surpluses for several years now, the LAO expects another surplus for the FY2020-21 budget – albeit a slightly smaller $7 billion surplus. Even more promising, the LAO predicts that should the economy remain strong, the state will continue to run $3 billion surpluses for the foreseeable future. Should a recession hit, the LAO believes that the state has ample reserves to cover the revenue shortfalls that accompany a typical post-World War II recession.

Yet, these rosy predictions gloss over some very troubling trends. Based on California’s budget history, the state’s future fiscal health is more precarious than these rosy scenarios indicate.

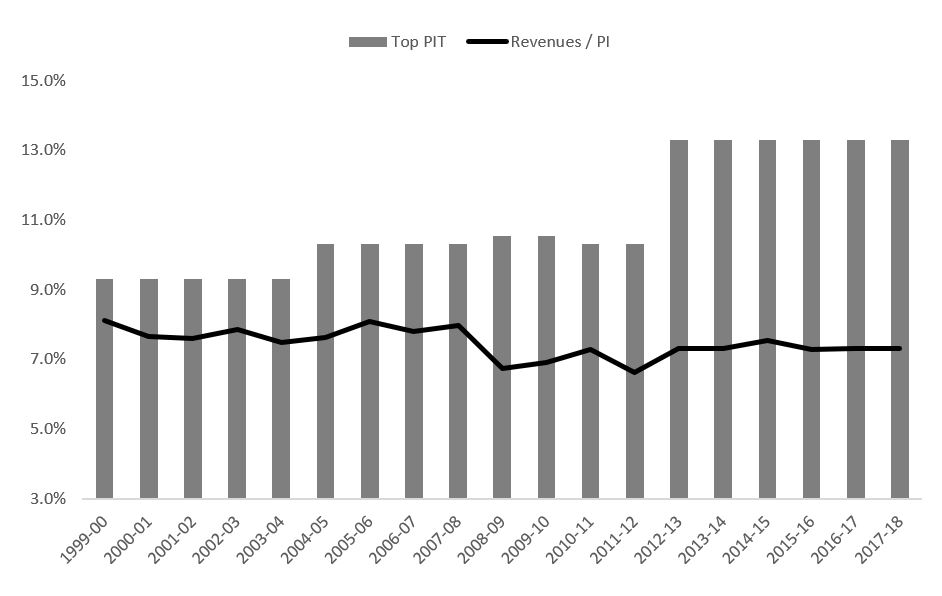

The Figure below compares the percent change in California’s personal income (the gray dotted line) to the percent change in total California government revenues (the solid black line). The Figure clearly illustrates that California’s government revenues are dependent on a strong economy. Perhaps just as important, the Figure illustrates that state government’s revenues exhibit significantly more volatility than the economy.

This volatility is a direct result of the state’s progressive tax system that causes revenues to surge during the economic boom, but then crash harder than the economy during recessions. A predictable budget cycle emerges. During the periods of economic growth (like today) the budget is flush with revenues, which are quickly spent by the Legislature. When the inevitable economic downturn comes, the state is troubled with budget deficits for years.

This volatility is a direct result of the state’s progressive tax system that causes revenues to surge during the economic boom, but then crash harder than the economy during recessions. A predictable budget cycle emerges. During the periods of economic growth (like today) the budget is flush with revenues, which are quickly spent by the Legislature. When the inevitable economic downturn comes, the state is troubled with budget deficits for years.

Take the last downturn as the example. Once the economy fell into a recession, personal income tax revenues and total state government revenues in the 2008-09 fiscal year collapsed by $11.4 billion and by $20.9 billion, respectively. The fiscal problems for the state were even worse than these dire numbers indicate because the state budget was predicated on growing revenues. The result was persistent budget woes for years following the Great Recession.

So, what is bad about this? Isn’t the purpose of the rainy-day fund to cover the budget deficits that naturally occur during difficult economic times? In fact, there are two major budget problems exacerbated by this budget volatility that now threaten the state’s long-term fiscal health.

First, this pattern of booms and busts encourage unaffordable growth in California’s state government. The last budget cycle exemplifies the problem. Through the full economic cycle (from the FY2000-01 budget through the FY2008-09 budget) total expenditures grew 3.0 percent annually compared to 2.3 percent growth in state revenues. Put simply, the strong revenues during the good times encourage spending growth that appears to be affordable but is not once the impacts from economic downturns are considered.

Second, the strong revenue growth and growing rainy day fund makes it appear that California’s long-term fiscal health is sound. It is not. When properly valued, California’s unfunded pension liabilities, which does not include the value of promised health care benefits, could exceed $1 trillion. Due to these large unfunded liabilities, California is facing massive budget crises in the not-too-distant future.

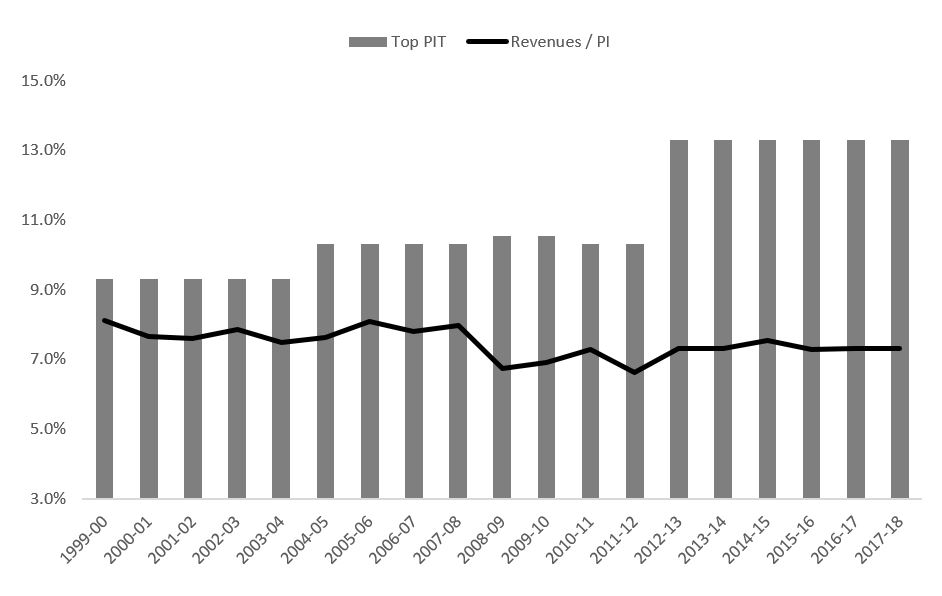

As a final bearish observation, the effectiveness of California’s tax system is degrading. Exemplifying this problem are the total state government revenues raised relative to personal income. Marginal personal income tax rates were increased in response to the last revenue crisis, yet total California state-based revenues relative to personal income have decreased to multi-decade lows (8.1% in the 1999-00 FY, but 7.3% in 2017-18, both periods are times of economic growth), see the Figure below. This decline is a sign that taxpayers have altered their behavior in response to these higher tax rates such that the government is raising less revenue per dollar of income despite the higher rates.

The combination of these trends is a foreboding sign for California’s fiscal position when the next economic recession occurs. Personal income in recessions fall (by definition). As is typical for California, state revenues will crash even harder than personal income. Since tax revenues are a smaller share of personal income, this crash in government revenues will likely be even more severe. Consequently, despite the buildup in the state rainy day funds, significant budget shortfalls are a greater risk than is currently being recognized.

The combination of these trends is a foreboding sign for California’s fiscal position when the next economic recession occurs. Personal income in recessions fall (by definition). As is typical for California, state revenues will crash even harder than personal income. Since tax revenues are a smaller share of personal income, this crash in government revenues will likely be even more severe. Consequently, despite the buildup in the state rainy day funds, significant budget shortfalls are a greater risk than is currently being recognized.

The existence of these risks demonstrate that the state should focus on improving growth incentives, establishing a less volatile tax system, and addressing its long-term budget shortfalls. Without such fundamental reforms, the current rosy budget scenarios will be short-lived.

Dr. Wayne Winegarden is senior fellow in business and economics at the Pacific Research Institute, and the director of PRI’s Center for Medical Economics and Innovation.