It’s hard not to love Larry Baer, the CEO of the San Francisco Giants. He is the team’s public face and cheerleader in chief – a proud San Franciscan with diplomas from Lowell High School and Cal Berkeley that attest to his deep Bay Area roots. And no one can spin the failure to land baseball phenoms Shohei Ohtani and Yoshinobu Yamamoto in the off-season (both now wearing Dodger blue) like Larry.

Recently, he spoke at a Commonwealth Club event pitching the team’s “Betting Big on the City” plan, encompassing the Mission Rock project just across McCovey Cove from the ballpark. It’s a $2.5 billion bet in the form of a mixed residential, corporate and retail development. A San Francisco Chronicle article running the day after his speech shows it will take every ounce of chutzpah Baer can summon as the city faces another public health crisis.

That story was one that has become all too familiar to anyone who has walked in the Tenderloin, Mission, or South of Market (SOMA) neighborhoods: public defecation.

The Chronicle reports that there were 32,234 feces complaints made to San Francisco’s public service 311 system in 2023, up from 25,771 in 2018.

Temple University Professor Bryant Simon, who is writing a book about the history of public toilets in America, said public toilet availability declined in the 20th century, disappearing for “simple and sinister” reasons.

“We got rid of them to disappear the people who used them who we thought were a problem. Now you have open defecation, which everyone is affected by and we’re using bathrooms to try to put a Band-Aid on the problem.”

Who were those people? According to Simon, they are “people of color and the unhoused.”

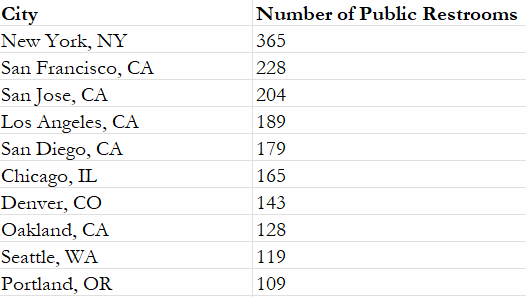

It’s true that people of color are overrepresented in the homeless and addicted population, but 75 percent of California’s homeless population are white. Meanwhile, a study from the City of Portland shows San Francisco and four other California cities rank among the nation’s top 10 cities for public restroom access.

San Francisco provides over 30 staffed “pit stops” mostly located in the neighborhoods surrounding Mission Rock. Many are staffed 24/7 but most do close overnight.

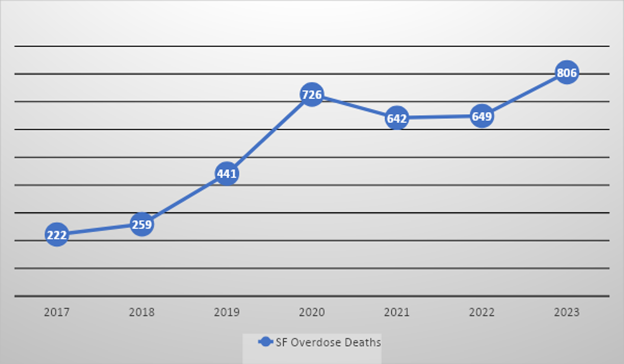

Perhaps the chief cause of the public restroom problem is another category where San Francisco leads the nation: opioid addiction and overdose deaths, mostly caused by fentanyl abuse and addiction.

The increases in public defecation complaints and opiate deaths are no coincidence. When an addict is coming off their “high” and going through withdrawals, severe uncontrollable diarrhea can occur. Addicts become so ill that they simply do not care when or where they defecate, much less “hold it” until they reach a staffed pit stop.

As one can imagine, when the pit stops are used the work to keep them clean is considerable. San Francisco Public Works partners with two non-profits Civic and Hunters Point Family, to operate the pit stops. Their main source of staffing is former prison inmates. I don’t think that was the kind of employment envisioned by progressives who bought into Sacramento’s decarceration and rehabilitation agenda.

Worldwide, human feces and poor sanitation are the primary drivers of the spread of cholera, killing thousands every year. While the threat of cholera is currently low in the United States, vibriosis and shigella are here.

Feces in San Francisco are sometimes collected and disposed of in landfills, but often they are washed off the sidewalks and into the storm drain system. There, it eventually winds up in San Francisco Bay and the Pacific Ocean as untreated sewage, potentially contaminating sea-life habitat and posing a health threat to swimmers and bathers with open cuts or who may ingest seawater.

This is a consequence of the failure of California to properly address illegal and dangerous drug use and homelessness problems that go back over 25 years and have been made more acute by the advent of street level use of fentanyl.

The myth of dramatically reducing prison populations to create budgetary windfalls that would be used on treatment and education is proving to be a budgetary shell game of accounting trickery. Both the State and their non-profit partners who have been the recipients of billions in drug treatment and homeless funding share the responsibility for this failure.

The BS in Sacramento is piling up all the way to the streets of San Francisco – and it will take more than the optimism of Larry Baer to fix it.

Steve Smith is a senior fellow in urban studies at the Pacific Research Institute.