Spiraling pension costs still crowding out city services

by Edward Ring

About 20 years ago, I read an ad in a local Sacramento newspaper that said, “Get a government job and become an instant millionaire.” The ad described how public officials in California enjoyed benefits private sector employees can rarely attain, including a guaranteed pension worth millions of dollars in a 401k plan. I’d had no idea. Most people still don’t have a clue.

The effect of pension obligations on government budgets remains one of the most consequential elements of public policy that few people know about. The typical response to pension policy debates is one of befuddlement or indifference – until someone is elected to a city council, or a county board of supervisors, and sees first-hand how pension payments crowd out other budget items.

Also about 20 years ago, California legislators – egged on by aggressive pension system managers and public employee unions – enacted a series of pension benefit enhancements, via Senate Bill 400. That moved pension payments from a negligible portion of civic budgets to ravenous monsters that threatened to drive into insolvency nearly every city.

The result has been higher taxes and fewer services, and everyone feels its sting. Quite simply, cities have been cutting back on community services, park systems, road improvements, arts funding and police staffing levels to pay for their retirees.

To begin to cope with out-of-control pension costs, in 2013 the California Legislature enacted PEPRA, the Public Employee Pension Reform Act, which reduced the pension benefit formulas for new government hires. It phased in a cost sharing whereby all active employees would contribute more to their pension systems via payroll withholding. It was signed by then-Gov. Jerry Brown.

The PEPRA reform, while incremental, helped financially stabilize California’s public-sector pension systems. Because PEPRA reforms were primarily restricted to new hires, the savings will happen slowly and take decades to be fully realized. Meanwhile, the cost to California’s cities and counties to pay their pensions has reached record heights.

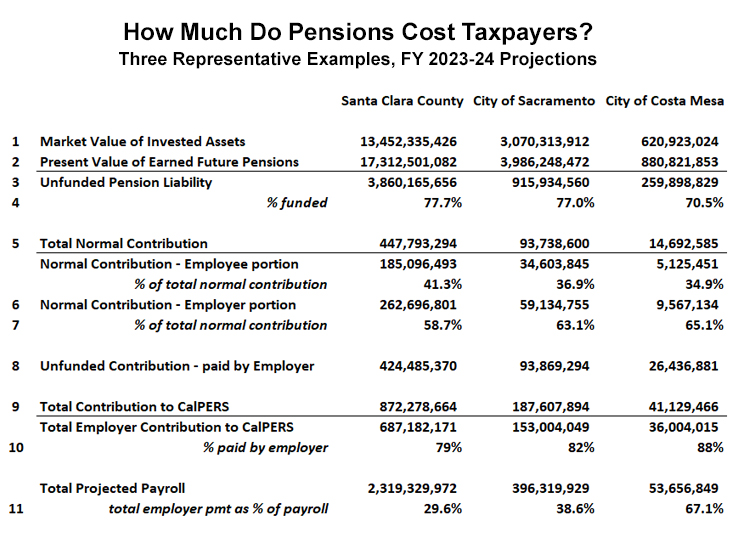

To more thoroughly illustrate what California’s government agencies are up against, the attached chart depicts the financial status of three representative entities, each of them a rough order of magnitude apart in size. All three are clients of the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, the largest of California’s state and local pension systems. It has nearly 1,700 active clients and assets that have exceeded $500 billion.

The statistics, although opaque to the uninitiated, nonetheless distill the financial obligation represented by pensions to a few key variables. All figures come directly from CalPERS. For each of its clients, CalPERS provides a “Public Agency Actuarial Valuation Report.” These are highly reliable reports because they disclose exactly how much CalPERS intends to charge each of its clients. The data shown on the chart pertains to the 2023-2024 fiscal year, which begins in July 2023.

The first three rows of data on the above chart report 1) how much CalPERS has invested on behalf of each client; 2) the present value of how much CalPERS expects at this time to eventually pay out in pensions to each client’s retirees; and 3) the difference between these two values, which is the unfunded pension liability, or debt.

As shown in line 4, Santa Clara County and the city of Sacramento have only 77 percent funded pension accounts, and Costa Mesa’s pension account is only 70 percent funded. That means they only have 70 percent to 77 percent of the funds available to meet all of their promises. In addition to their ongoing payments to fund earned pension benefits, these employers have to make catch-up payments to reduce their unfunded liability.

The next section depicts and quantifies these two types of contributions that agencies must make to their pension system. The so-called “Normal Contribution” (5) is how much money they must pay to the pension system and invest each year to yield sufficient funds to eventually pay the additional pension benefits earned by active employees in that year.

In line 7, we see that the employers – i.e., the taxpayers – pay about two-thirds of the normal contribution. The PEPRA reform requires employees to pay half of the pension cost through payroll withholding, but, again, PEPRA only affects those hired after 2013. This means that in a few decades the taxpayer share of the normal contribution will come down to 50 percent.

The “unfunded contribution” (8) is what cities and counties must pay to reduce their unfunded liability. For that amount, no employee contribution is required. The employer has to pay 100 percent. In all cases, the unfunded contribution is far more than the normal contribution (row 8 compared to row 6). This means the employer share is 79 percent of Santa Clara County’s total pension payment obligation, 82 percent of Sacramento’s, and 88 percent of Costa Mesa’s (row 10).

We can put this burden in context when considering how much these costs add to an agency payroll. The total employer payment for their pensions adds 29 percent to payroll costs in Santa Clara County, 38 percent in Sacramento, and a whopping 67 percent in Costa Mesa (11).

This represents a huge opportunity cost. For perspective, consider the impact of transitioning every public employee to Social Security. At a cost to the employer of 6.2 percent of payroll, Santa Clara County would save $543 million per year, Sacramento would save $128 million, and Costa Mesa would save $32 million. This is considered a radical idea, but it puts the pension costs in perspective. Isn’t Social Security what private sector taxpayers must rely upon for their retirement security?

Let’s take this thought experiment one step further. Even if along with the Social Security payment, cities added an additional 6.2 percent of salary to be the employer’s contribution to each employee’s 401K – a level of generosity rarely found in the private sector – taxpayers would still save, per year, $399 million in Santa Clara County, $103 million in Sacramento, and $29 million in Costa Mesa.

Those dollars would fund an almost incomprehensible level of city services. How far would $399 million would go towards repairing the roads in Santa Clara County, which are ranked among the worst in the nation, using data from the Federal Highway Administration. Consider how that money could be invested in more law enforcement, when violent crime has increased for the past two years in Santa Clara County.

In Sacramento, investing another $103 million in basic law enforcement would go a long way towards curbing violent crime in that city, where homicides were up over 30 percent in 2021 compared to 2021, and are on track in 2022 to exceed that in 2023.

How many shelter beds could $103 million buy, as the homeless count in Sacramento County – most of them concentrated in the city of Sacramento – nearly doubled between 2019 and 2022? As it is, Sacramento’s projected $153 million outlay for pension contributions to CalPERS is more than they will spend on all of their capital improvement programs this year.

Costa Mesa might only save $29 million by replacing defined benefit pensions with a combination of Social Security and an exceedingly generous 401K plan. With only 110,000 residents, Costa Mesa isn’t a very big city. The city’s general fund budget for 2022-23 is $163 million. Saving $29 million would add 17 percent to the city’s budget to tackle other challenges. By the way, the state auditor puts that city near the highest on its “at risk” list regarding pension obligations.

It is easy to criticize how California’s public agencies would spend the money they could save. These agencies are notoriously inefficient as they address the homelessness crisis. More spending on law enforcement is wasted if criminals aren’t held accountable. Road improvement projects are plagued by misspending. But these examples of waste don’t obviate the fact that pension commitments have swamped civic budgets.

Pension systems in California’s state and local government agencies today have achieved a precarious stability, thanks in part to PEPRA, and for the most part thanks to dramatically higher contributions demanded from taxpayers. But this stability has come at a terrific price in the form of lost opportunities for these agencies to better serve the public.

Edward Ring is a co-founder of the California Policy Center and the author of “The Abundance Choice: Our Fight for More Water in California.”