California’s 2018 crime data has been released and the news is mostly encouraging, though a bit mixed.

The violent crime rate is slightly down (1.5%) after growing for three straight years, and four of the last seven, according to data released this month by the state Department of Justice. Homicides have fallen for two straight years. Robbery decreased after growing for three consecutive years.

Overall property crime rates fell (5.1%), as well, for the third consecutive year.

In the three previous years, the trend had been moving in the wrong direction following historically low violent crime rates of 2013 and 2014.

The good news, however, is offset somewhat by increased rates in rape, which have been growing for five years, and now have reached 38.9 per 100,000 population.

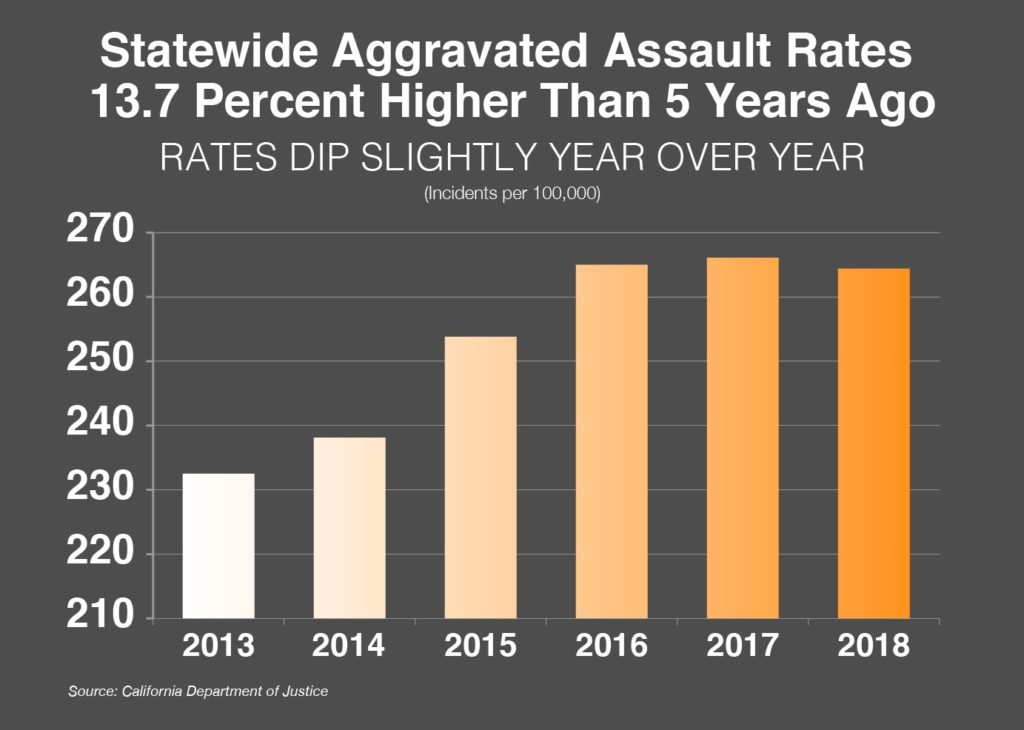

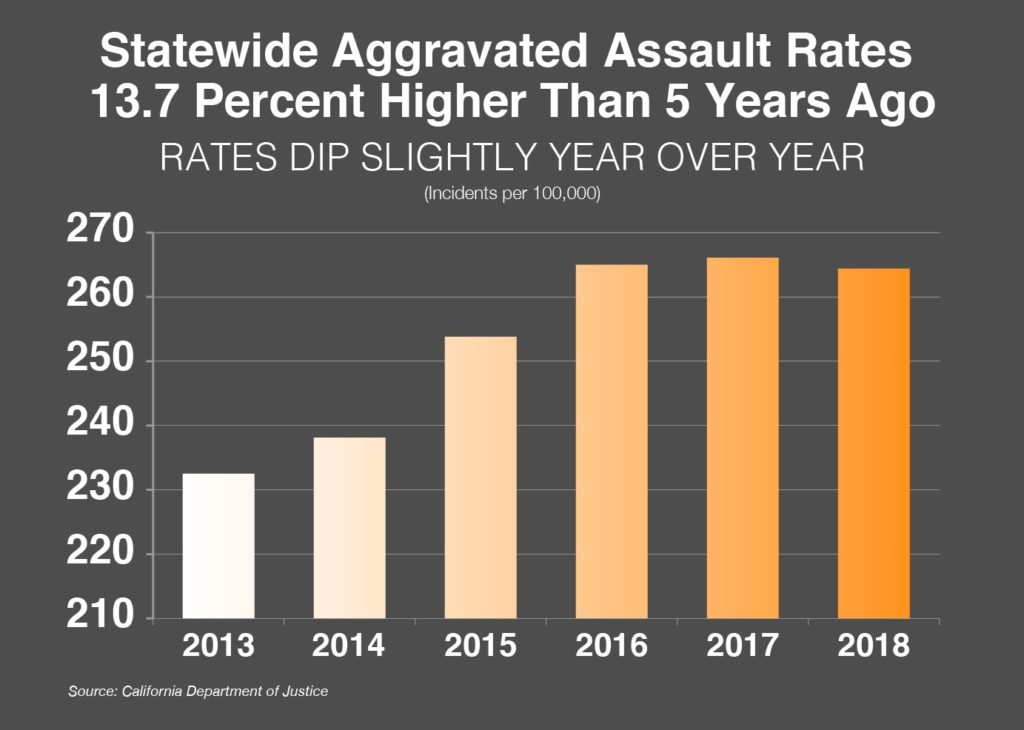

While there have been improvements, the violent crime rate was still higher in 2018 than in 2013, 444.1 incidents per 100,000 compared to 396.9, nearly a 12% difference. The aggravated assault rate also was higher last year than it was five years prior.

While there have been improvements, the violent crime rate was still higher in 2018 than in 2013, 444.1 incidents per 100,000 compared to 396.9, nearly a 12% difference. The aggravated assault rate also was higher last year than it was five years prior.

Meanwhile, the property crime rate was 11.4% lower in 2018 than in 2013.

Data can’t capture the entire picture, though. Many Californians say that despite the numbers, they still feel more threatened than they had in the past. We can’t discount the likelihood that the perception is entirely warranted because crime, both violent and property, has increased in some areas.

The Santa Monica Mirror reports that “serious” crime in that city increased 8.8% last year over 2017. Violent crime rose 6% in San Jose, burglaries about 17%. Though San Diego’s violent crime rate was “one of the lowest rates in the last four decades, homicides and rapes were up, according to a new study from the San Diego Association of Governments.”

In downtown Los Angeles, “crime reports jumped by 10.4%” in 2018, while in the West Los Angeles communities of Venice, Mar Vista, Westchester and Playa del Rey, overall crime grew more than 11 percent%.

And there is still concern over “a growing epidemic” of rural crime, where as many as three-fourths of the incidents go unreported, says Hoover Institution fellow Victor Davis Hanson, because victims “know the authorities are short-handed or that little will be done to those if caught.”

So, while there’s reason to be optimistic, lawmakers and government officials still have work ahead.

Kerry Jackson is a fellow with the Center for California Reform at the Pacific Research Institute.